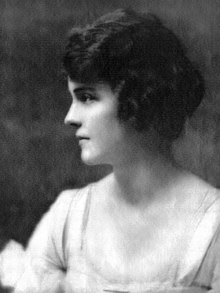

Ginevra King | |

|---|---|

A 20-year-old Ginevra King on the July 1918 cover of Town & Country magazine | |

| Born | November 30, 1898 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 13, 1980 (aged 82) |

| Burial place | Lake Forest Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Westover School (expelled) |

| Occupation | Socialite |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

|

Ginevra King Pirie (November 30, 1898 – December 13, 1980) was an American socialite and heiress.[1] As one of the self-proclaimed "Big Four" debutantes of Chicago during World War I,[2] King inspired many characters in the novels and short stories of Jazz Age writer F. Scott Fitzgerald; in particular, the character of Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.[3] A 16-year-old King met an 18-year-old Fitzgerald at a sledding party in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and they shared a passionate romance from 1915 to 1917.[4]

Although King was "madly in love" with Fitzgerald,[5] their relationship ended when King's family intervened.[6] Her father Charles Garfield King purportedly warned the young writer that "poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls",[7][8] and he forbade further courtship of his daughter by Fitzgerald.[a][9] A heartbroken Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton University and enlisted in the United States Army amid World War I.[10][11] While courting his future wife Zelda Sayre and other young women while garrisoned near Montgomery, Alabama, Fitzgerald continued to write to King in the hope of rekindling their relationship.[12]

While Fitzgerald served in the army, King's father arranged her marriage to William "Bill" Mitchell [wd], the son of his wealthy business associate John J. Mitchell.[13][14] An avid polo player, Bill Mitchell became the director of Texaco,[15] and he partly served as the model for Thomas "Tom" Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.[b][16] Despite King marrying Mitchell and Fitzgerald marrying Zelda Sayre, Fitzgerald remained forever in love with King until his death.[17][18] Fitzgerald scholar Maureen Corrigan notes that King, far more so than the author's wife Zelda Sayre, became "the love who lodged like an irritant in Fitzgerald's imagination, producing the literary pearl that is Daisy Buchanan".[19] In the mind of Fitzgerald, King became the prototype of the unobtainable, upper-class woman who embodies the elusive American Dream.[20]

During her relationship with Fitzgerald, Ginevra wrote a Gatsby-like story which she sent to the young author.[21] In her story, she is trapped in a loveless marriage with a wealthy man yet still pines for Fitzgerald.[21] The lovers are reunited only after Fitzgerald attains enough money to take her away from her adulterous husband.[21] Fitzgerald kept Ginevra's story with him, and scholars have noted the plot similarities between Ginevra's story and Fitzgerald's novel.[22]

King separated from Mitchell in 1937 after an unhappy marriage.[23][24] A year later, Fitzgerald attempted to reunite with King when she visited Hollywood in 1938.[25] The reunion proved a disaster due to Fitzgerald's alcoholism, and a disappointed King returned to Chicago.[25][26] She later married John T. Pirie Jr., a business tycoon and owner of the Chicago department retailer Carson Pirie Scott & Company.[27] She died in 1980 at the age of 82 at her estate in Charleston, South Carolina.[27]

- ^ Diamond 2012; Bleil 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Diamond 2012; Corrigan 2014, p. 59; Rothman 2012, p. K12.

- ^ Borrelli 2013; Bleil 2008, p. 43; McKinney 2017; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 53–59; Corrigan 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Smith 2003, p. E1; Corrigan 2014, p. 61; McKinney 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ginevra's Lovewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Smith 2003, p. E1; Corrigan 2014, p. 61; Dern 2011.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Poor Boys Iwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Poor Boys IIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dern 2011; Corrigan 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Mizener 1965, p. 70; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 80, 82.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Heartbrokenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ West 2005, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Arranged Marriagewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Chicago Tribune 1987, p. 30; Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9–11, 246; Bruccoli 2002, p. 86; West 2005, pp. 66–70; Engagement Announcement 1918, p. 15.

- ^ Mitchell Obituary 1987, p. 30; Chicago Tribune 1987, p. 30; West 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 86; Noden 2003.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lifelong Obsessionwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stevens 2003; Noden 2003.

- ^ Corrigan 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Stepanov 2003.

- ^ a b c West 2005, pp. 3, 50–51, 56–57.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Similaritywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ McKinney 2017.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Marital Discordwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b West 2005, pp. 86–87; Corrigan 2014, p. 59; Smith 2003, p. E1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Alcoholismwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Bleil 2008, p. 38; McKinney 2017.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).