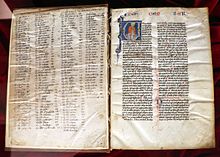

Legenda Aurea, c. 1290, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence | |

| Author | Jacobus de Voragine |

|---|---|

| Original title | Legenda aurea |

| Translator | William Caxton Frederick Startridge Ellis |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | hagiography |

Publication date | 1265 |

| Publication place | Genoa |

Published in English | 1483 |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| OCLC | 821918415 |

| 270.0922 | |

| LC Class | BX4654 .J334 |

Original text | Legenda aurea at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | Golden Legend at Wikisource |

The Golden Legend (Latin: Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum) is a collection of 153 hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that was widely read in Europe during the Late Middle Ages. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived.[1] It was probably compiled around 1259 to 1266, although the text was added to over the centuries.[2][3]

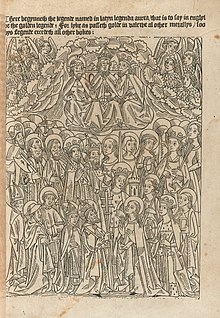

Initially entitled Legenda sanctorum (Readings of the Saints), it gained its popularity under the title by which it is best known. It overtook and eclipsed earlier compilations of abridged legendaria, the Abbreviatio in gestis et miraculis sanctorum attributed to the Dominican chronicler Jean de Mailly and the Epilogus in gestis sanctorum of the Dominican preacher Bartholomew of Trent. When printing was invented in the 1450s, editions appeared quickly, not only in Latin, but also in almost every major European language.[4] Among incunabula, printed before 1501, Legenda aurea was printed in more editions than the Bible[5] and was one of the most widely published books of the Middle Ages.[6] During the height of its popularity the book was so well known that the term "Golden Legend" was sometimes used generally to refer to any collection of stories about the saints.[7] It was one of the first books William Caxton printed in the English language; Caxton's version appeared in 1483 and his translation was reprinted, reaching a ninth edition in 1527.[8]

Written in simple, readable Latin, the book was read in its day for its stories. Each chapter is about a different saint or Christian festival. The book is considered the closest thing to an encyclopaedia of medieval saint lore that survives today; as such, it is invaluable to art historians and medievalists who seek to identify saints depicted in art by their deeds and attributes. Its repetitious nature is explained if Jacobus meant to write a compendium of saintly lore for sermons and preaching, not a work of popular entertainment.

- ^ Hilary Maddocks, "Pictures for aristocrats: the manuscripts of the Légende dorée", in Margaret M. Manion, Bernard James Muir, eds. Medieval texts and images: studies of manuscripts from the Middle Ages 1991:2; a study of the systemization of the Latin manuscripts of the Legenda aurea is B. Fleith, "Le classement des quelque 1000 manuscrits de la Legenda aurea latine en vue de l'éstablissement d'une histoire de la tradition" in Brenda Dunn-Lardeau, ed. Legenda Aurea: sept siècles de diffusion, 1986:19–24

- ^ An introduction to the Legenda, its great popular late medieval success and the collapse of its reputation in the 16th century, is Sherry L. Reames, The Legenda Aurea: a reexamination of its paradoxical history, University of Wisconsin, 1985.

- ^ Hamer 1998:x

- ^ Hamer 1998:xx

- ^ Reames 1985:4

- ^ Hamer 1998:ix

- ^ Hamer 1998:xvii

- ^ Jacobus (de Vorágine) (1973). The Golden Legend. CUP Archive. pp. 8–. GGKEY:DE1HSY5K6AF. Retrieved 16 November 2012.