Voivode Gotse Delchev | |

|---|---|

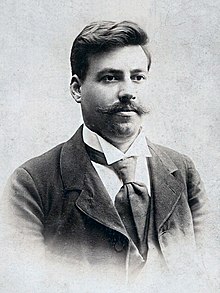

Portrait of Gotse Delchev in Sofia c. 1900 | |

| Native name | Гоце Делчев |

| Birth name | Georgi Nikolov Delchev |

| Born | 4 February 1872 Kukush,[1] Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 4 May 1903 (aged 31) Banitsa, Ottoman Empire |

| Buried | Banitsa (1903-1913) Xanthi (1913-1919) Plovdiv (1919-1923) Sofia (1923-1946) Church of the Ascension of Jesus, Skopje (since 1946) |

| Service | Bulgarian army Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee |

| Alma mater | Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki Military School of His Princely Highness |

| Other work | Teacher |

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian: Георги Николов Делчев; Macedonian: Ѓорѓи Николов Делчев; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (Гоце Делчев),[note 1] was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji),[2] active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions, as well as in Bulgaria, at the turn of the 20th century.[3][4][5] He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.[6] Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria.[7] As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC),[8] participating in the work of its governing body.[9] He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Born into a Bulgarian family in Kilkis,[10][11] then in the Salonika vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, in his youth he was inspired by the ideals of earlier Bulgarian revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev, who envisioned the creation of a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, as part of an imagined Balkan Federation.[12] Delchev completed his secondary education in the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki and entered the Military School of His Princely Highness in Sofia, but he was dismissed from there, only a month before his graduation, because of his leftist political persuasions. Then he returned to Ottoman Macedonia as a Bulgarian teacher,[13] and immediately became an activist of the newly-found revolutionary movement in 1894.[14]

Although considering himself to be an inheritor of the Bulgarian revolutionary traditions,[15] he opted for Macedonian autonomy.[16] Also for him, like for many Macedonian Bulgarians, originating from an area with mixed population,[17] the idea of being 'Macedonian' acquired the importance of a certain native loyalty, that constructed a specific spirit of "local patriotism"[18][19] and "multi-ethnic regionalism".[20][21] He maintained the slogan promoted by William Ewart Gladstone, "Macedonia for the Macedonians", including all different nationalities inhabiting the area.[22][23][1] In this way, his outlook included a wide range of such disparate ideas like Bulgarian patriotism, Macedonian regionalism, anti-nationalism, and incipient socialism.[24][25] As a result, his political agenda became the establishment through revolution of an autonomous Macedono-Adrianople supranational state into the framework of the Ottoman Empire, as a prelude to its incorporation within a future Balkan Federation.[26] Despite having been educated in the spirit of Bulgarian nationalism, he revised the Organization's statute, where the membership was allowed only for Bulgarians.[27] In this way he emphasized the importance of cooperation among all ethnic groups in the territories concerned in order to obtain political autonomy.[14]

Today Gotse Delchev is considered a national hero in Bulgaria and North Macedonia. Because his autonomist ideas have stimulated the subsequent development of Macedonian nationalism,[28] in the latter it is claimed he was an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary. Thus, Delchev's legacy remains disputed between both countries. Nevertheless, some researchers think, that behind IMRO's idea of autonomy was hidden a reserve plan for eventual incorporation into Bulgaria.[29][30][31] Per some of his contemporaries and some Bulgarian sources, Delchev supported Macedonia's incorporation into Bulgaria as another option too. However, other researchers find the identity of Delchev and other IMRO figures to be "open to different interpretations",[32] that are incompatible with the views of modern Balkan nationalisms.[33]

- ^ a b Anastasia Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990, University of Chicago Press, 2009, ISBN 0226424995, p. 282.

- ^

- Danforth, Loring. "Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

IMRO was founded in 1893 in Thessaloníki; its early leaders included Damyan Gruev, Gotsé Delchev, and Yane Sandanski, men who had a Macedonian regional identity and a Bulgarian national identity.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0691043566.

The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard Misirkov's call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarian rather than Macedonians. (...) In spite of these political differences, both groups, including those who advocated an independent Macedonian state and opposed the idea of a greater Bulgaria, never seem to have doubted "the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia". (...) Even Gotse Delchev, the famous Macedonian revolutionary leader, whose nom de guerre was Ahil (Achilles), refers to "the Slavs of Macedonia as 'Bulgarians' in an offhanded manner without seeming to indicate that such a designation was a point of contention" (Perry 1988:23). In his correspondence Gotse Delchev often states clearly and simply, "We are Bulgarians" (Mac Dermott 1978:273).

- Perry, Duncan M. (1988). The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780822308133.

- Victor Roudometof (2002). Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 79. ISBN 0275976483. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Danforth, Loring. "Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 0691188432, p. 174; Bernard Lory, The Bulgarian-Macedonian Divergence, An Attempted Elucidation, INALCO, Paris in Developing Cultural Identity in the Balkans: Convergence Vs. Divergence with Raymond Detrez and Pieter Plas as ed., Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 9052012970, pp. 165-193.

- ^ The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary, Hugh Seton-Watson, Christopher Seton-Watson, Methuen, 1981, ISBN 0416747302, p. 71.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. VII.

- ^ Bechev, Dimitar (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1., pp. 55-56.

- ^ Angelos Chotzidis, Anna Panagiōtopoulou, Vasilis Gounaris, The events of 1903 in Macedonia as presented in European diplomatic correspondence. Volume 3 of Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, 1993; ISBN 9608530334, p. 60.

- ^ From 1899 to 1901, the supreme committee provided subsidies to IMRO's central committee, allowances for Delchev and Petrov in Sofia, and weapons for bands sent to the interior. Delchev and Petrov were elected full members of the supreme committee. For more see: Laura Beth Sherman, Fires on the Mountain: The Macedonian Revolutionary Movement and the Kidnapping of Ellen Stone, East European monographs, 1980, ISBN 0914710559, p. 18.

- ^ Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903; Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 82-83.

- ^ Susan K. Kinnell, People in World History, Volume 1; An Index to Biographies in History Journals and Dissertations Covering All Countries of the World Except Canada and the U.S, ISBN 0874365503, ABC-CLIO, 1989; p. 157.

- ^ Delchev was born into a family of Bulgarian Uniates, who later switched to Bulgarian Еxarchists. For more see: Светозар Елдъров, Униатството в съдбата на България: очерци из историята на българската католическа църква от източен обред, Абагар, 1994, ISBN 9548614014, стр. 15.

- ^ Jelavich, Charles. The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920, University of Washington Press, 1986, ISBN 0295803606, pp. 137-138.

- ^ Julian Brooks, The Education Race for Macedonia, 1878—1903 in The Journal of Modern Hellenism, Vol 31 (2015) pp. 23-58.

- ^ a b Raymond Detrez, The A to Z of Bulgaria, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 0810872021, p. 135.

- ^ Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 39-40.

- ^ Todorova, Maria N. Bones of Contention: The Living Archive of Vasil Levski and the Making of Bulgaria's National Hero, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776246, pp. 76-77.

- ^ "The French referred to 'Macedoine' as an area of mixed races — and named a salad after it. One doubts that Gotse Delchev approved of this descriptive, but trivial approach." Johnson, Wes. Balkan inferno: betrayal, war and intervention, 1990-2005, Enigma Books, 2007, ISBN 1929631634, p. 80.

- ^ "The Bulgarian historians, such as Veselin Angelov, Nikola Achkov and Kosta Tzarnushanov continue to publish their research backed with many primary sources to prove that the term 'Macedonian' when applied to Slavs has always meant only a regional identity of the Bulgarians." Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 112.

- ^ "Gotse Delchev, may, as Macedonian historians claim, have 'objectively' served the cause of Macedonian independence, but in his letters he called himself a Bulgarian. In other words it is not clear that the sense of Slavic Macedonian identity at the time of Delchev was in general developed." Moulakis, Athanasios. "The Controversial Ethnogenesis of Macedonia", European Political Science (2010) 9, ISSN 1680-4333. p. 497.

- ^ "Slavic Macedonian intellectuals felt loyalty to Macedonia as a region or territory without claiming any specifically Macedonian ethnicity. The primary aim of this Macedonian regionalism was a multi-ethnic alliance against the Ottoman rule." Ethnologia Balkanica, vol. 10–11, Association for Balkan Anthropology, Bŭlgarska akademiia na naukite, Universität München, Lit Verlag, Alexander Maxwell, 2006, p. 133.

- ^ "The Bulgarian loyalties of IMRO's leadership, however, coexisted with the desire for multi-ethnic Macedonia to enjoy administrative autonomy. When Delchev was elected to IMRO's Central Committee in 1896, he opened membership in IMRO to all inhabitants of European Turkey since the goal was to assemble all dissatisfied elements in Macedonia and Adrianople regions regardless of ethnicity or religion in order to win through revolution full autonomy for both regions." Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2009, ISBN 3825813878, p. 136.

- ^ Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5., p. 56

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov, We, the Macedonians, The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912) in: Mishkova Diana ed., 2009, We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Central European University Press, ISBN 9639776289, pp. 117-120. Archived 17 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peter Vasiliadis (1989). Whose are you? identity and ethnicity among the Toronto Macedonians. AMS Press. p. 77. ISBN 0404194680. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ The earliest document which talks about the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace into the Ottoman Empire is the resolution of the First congress of the Supreme Macedonian Committee held in Sofia in 1895. От София до Костур -освободителните борби на българите от Македония в спомени на дейци от Върховния македоно-одрински комитет, Ива Бурилкова, Цочо Билярски - съставители, ISBN 9549983234, Синева, 2003, стр. 6.

- ^ Opfer, Björn (2005). Im Schatten des Krieges: Besatzung oder Anschluss - Befreiung oder Unterdrückung? ; eine komparative Untersuchung über die bulgarische Herrschaft in Vardar-Makedonien 1915-1918 und 1941-1944. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-7997-6., pp. 27-28

- ^ Laura Beth Sherman, Fires on the mountain: the Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen Stone, Volume 62, East European Monographs, 1980, ISBN 0914710559, p. 10.

- ^ Roumen Dontchev Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov. Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Balkan Studies Library, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X. pp. 300-303.

- ^ Anastasia Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990, University of Chicago Press, 2009, ISBN 0226424995, p. 100.

- ^ İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908, Cornell University Press, 2013, ISBN 0801469791, p. 16.

- ^ Dimitris Livanios, The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939-1949, Oxford Historical Monographs, OUP Oxford, 2008, ISBN 0191528722, p. 17.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides (2021). The Macedonian Question and The Macedonians. Taylor & Francis. p. 39.

As Keith Brown points out, 'for leaders like Goce Delčev, Pitu Guli, Damjan Gruev, and Jane Sandanski - the four national heroes named in the anthem of the modern Republic of Macedonia - the written record of what they believed about their own identity is open to different interpretations. The views and self-perceptions of their followers and allies were even less conclusive.'

- ^ Keith Brown uses terms like “Bulgar,” “Arnaut,” “Mijak” and “Exarchist” seeking in this way to remind the very different world of the late 19th century. For more see: The importance of ‘unlearning’ the past: Interview with Balkans expert Keith Brown. Global Voices, 28 October 2020. Archived 24 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).