| Grand Mosque seizure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

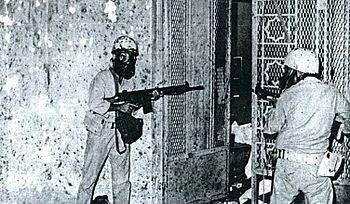

Saudi soldiers pushing into the underground corridor of the Grand Mosque of Mecca after gassing the interior with a non-lethal chemical agent provided by French specialists. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| N/A | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~10,000 troops | 300–600 militants[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

|

11 pilgrims killed 109 pilgrims injured | |||||||

Location within Saudi Arabia | |||||||

The Grand Mosque seizure, also known as the Siege of Calamity, was a siege that took place between 20 November and 4 December 1979 at the Grand Mosque of Mecca, the holiest Islamic site in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The building was besieged by up to 600 militants under the leadership of Juhayman al-Otaybi, a Saudi anti-monarchy Islamist from the Otaibah tribe. They identified themselves as "al-Ikhwan" (Arabic: الإخوان), referring to the religious Arabian militia[5] that had played a significant role in establishing the Saudi state in the early 20th century.

The insurgents took hostages from among the worshippers and called for an uprising against the House of Saud, decrying their pursuit of alliances with "Christian infidels" from the Western world, and stating that the Saudi government's policies were betraying Islam by attempting to push secularism into Saudi society. They also declared that the Mahdi (end of times) had arrived in the form of one of the militants' leaders, Muhammad Abdullah al-Qahtani.

Seeking assistance for their counteroffensive against the Ikhwan, the Saudis requested urgent aid from France, which responded by dispatching advisory units from the GIGN. After French operatives provided them with a special type of tear gas that dulls aggression and obstructs breathing, Saudi troops gassed the interior of the Grand Mosque and forced entry. They successfully secured the site after two weeks of fighting.[11]

In the process of retaking the Grand Mosque, the Saudi forces killed the self-proclaimed messiah al-Qahtani. Juhayman and 68 other militants were captured alive and later sentenced to death by Saudi authorities, being executed by beheading in public displays across a number of Saudi cities.[12][13] The Ikhwan's siege of the Grand Mosque, which had occurred amidst the Islamic Revolution in nearby Iran, prompted further unrest across the Muslim world. Large-scale anti-American riots broke out in many Muslim-majority countries after Iranian religious cleric Ruhollah Khomeini falsely claimed in a radio broadcast that the Grand Mosque seizure had been orchestrated by the United States and Israel.[14]

Following the attack, Saudi king Khalid bin Abdulaziz enforced a stricter system of Islamic law throughout the country[15] and also gave the ulama more power over the next decade. Likewise, Saudi Arabia's Islamic religious police became more assertive.[16]

- ^ "Attack on Kaba Complete Video". 23 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Da Lage, Olivier (2006) [1996]. "L'Arabie Saoudite, pays de l'islam". Géopolitique de l'Arabie Saoudite. Géoppolitique des Etats du monde (in French). Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Brussels, Belgium: Éditions Complexe. p. 34. ISBN 2-8048-0121-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ see also Prouteau, Christian (1998). Mémoires d'Etat (in French). Michel Lafon. pp. 265–277, 280. ISBN 978-2840983606.

- ^ Wright, Robin (December 1991). Van Hollen, Christopher (ed.). "Unexplored Realities of the Persian Gulf Crisis". Middle East Journal. 45 (1). Washington, D.C., United States of America: Middle East Institute: 23–29. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328237.

- ^ a b Lacey 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Wright 2006b, p. 101.

- ^ Wright 2006b, pp. 103–104.

- ^ "The Siege at Mecca". 2006. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Pierre Tristam, "1979 Seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca", About.com". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Block, William; Block, Paul Jr.; Craig Jr., John G.; Deibler, William E., eds. (10 January 1980). Written at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. "63 zealots beheaded for seizing mosque". World/Nation. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 53, no. 140. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America: P.G. Publishing Co. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved 21 January 2022 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ Benjamin, The Age of Sacred Terror (2002) p. 90

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

vadvwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mackey, Sandra. The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom. Updated Edition. Norton Paperback. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. 2002 (first edition: 1987). ISBN 0-393-32417-6 pbk., p. 234.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 149.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 155.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 48 "Those old men actually believed that the Mosque disaster was God's punishment to us because we were publishing women's photographs in the newspapers, says a princess, one of Khaled's nieces. The worrying thing is that the king [Khaled] probably believed that as well... Khaled had come to agree with the sheikhs. Foreign influences and bida'a were the problem. The solution to the religious upheaval was simple—more religion."