The Viscount Gladstone | |

|---|---|

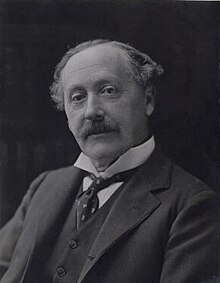

Gladstone c. 1910 | |

| 1st Governor-General of South Africa | |

| In office 31 May 1910 – 8 September 1914 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Louis Botha |

| Preceded by | Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson (as High Commissioner for Southern Africa) |

| Succeeded by | Sydney Buxton, 1st Earl Buxton |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 11 December 1905 – 19 February 1910 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Aretas Akers-Douglas |

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Herbert John Gladstone 7 January 1854 Downing Street Westminster, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 6 March 1930 (aged 76) Ware, Hertfordshire, England |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse |

Dorothy Mary Paget (m. 1901) |

| Children | 0 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | William Henry Gladstone (brother) Henry Gladstone (brother) Helen Gladstone (sister) |

| Alma mater | University College, Oxford |

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone, (7 January 1854 – 6 March 1930)[1][2] was a British Liberal politician. The youngest son of William Ewart Gladstone, he was Home Secretary from 1905 to 1910 and Governor-General of the Union of South Africa from 1910 to 1914.

Appointed whip in 1899, Gladstone was an innovator who provided a long-term strategy, kept the party from splitting over the Second Boer War, introduced more modern constituency structures; and encouraged working-class candidates. In secret meetings with Labour leaders in 1903 he forged the Gladstone–MacDonald pact. In two-member constituencies, it arranged that Liberal and Labour candidates did not split the vote. Historians give him much of the credit for the Liberal triumph in 1906, with 397 MPs and a majority of 243.[1]

Rising to Home Secretary in 1906–1908, he was responsible for the Workmen's Compensation Act 1906, a Factory and Workshops Act, and in 1908 the eight hour working day underground in the Coal Mines Regulation Act 1908. Historian John Grigg states that while his name is not often included in any list of radicals, his radical record is second to none in the Campbell-Bannerman Government. He was no firebrand but a good party man whose common sense inclined him to be less Gladstonian in the matter of state intervention then than his famous father had been. With his able under-secretary, Herbert Samuel, he sponsored no less than 34 Acts of Parliament during his time at the Home Office.[3]

- ^ a b "Gladstone, Herbert John, Viscount Gladstone". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33417. Retrieved 15 December 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Gladstone, 1st Viscount, (Herbert John Gladstone) (7 Jan. 1854–6 March 1930)". Who's Who & Who Was Who. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u210081. ISBN 978-0-19-954089-1. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ John Grigg, Lloyd George, the people's champion, 1902–1911 (1978). pp. 148–149.