| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

| folklore |

| Sport |

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The History of Pakistan prior to its independence in 1947 spans several millennia and covers a vast geographical area known as the Greater Indus region.[1] Anatomically modern humans arrived in what is now Pakistan between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.[2] Stone tools, dating as far back as 2.1 million years, have been discovered in the Soan Valley of northern Pakistan, indicating early hominid activity in the region.[3] The earliest known human remains in Pakistan are dated between 5000 BCE and 3000 BCE.[4] By around 7000 BCE, early human settlements began to emerge in Pakistan, leading to the development of urban centres such as Mehrgarh, one of the oldest in human history.[5][6] By 4500 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilization evolved, which flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE along the Indus River.[7] The region that now constitutes Pakistan served both as the cradle of a major ancient civilization and as a strategic gateway connecting South Asia with Central Asia and the Near East.[8][9]

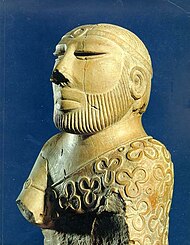

Situated on the first coastal migration route of Homo sapiens out of Africa, the region was inhabited early by modern humans.[10][11] The 9,000-year history of village life in South Asia traces back to the Neolithic (7000–4300 BCE) site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan,[12][13][14] and the 5,000-year history of urban life in South Asia to the various sites of the Indus Valley Civilization, including Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.[15][16]

Following the decline of the Indus valley civilization, Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia originally from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe in several waves of migration in the Vedic Period (1500–500 BCE), bringing with them came their distinctive religious traditions and Practices which fused with local culture.[17] The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the Bactria–Margiana culture and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.[18][note 1] Most notable among them was Gandhara civilization, which flourished at the crossroads of India, Central Asia, and the Middle East, connecting trade routes and absorbing cultural influences from diverse civilizations.[20] The initial early Vedic culture was a tribal, pastoral society centred in the Indus Valley, of what is today Pakistan. During this period the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed.[note 2]

The ensuing millennia saw the region of present-day Pakistan absorb many influences represented among others in the ancient, mainly Hindu-Buddhist, sites of Taxila, and Takht-i-Bahi, the 14th-century Islamic-Sindhi monuments of Thatta, and the 17th-century Mughal monuments of Lahore. In the first half of the 19th century, the region was appropriated by the East India Company, followed, after 1857, by 90 years of direct British rule, and ending with the creation of Pakistan in 1947, through the efforts, among others, of its future national poet Allama Iqbal and its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Since then, the country has experienced both civilian democratic and military rule, resulting in periods of significant economic and military growth as well as those of instability; significant during the latter, was the 1971 secession of East Pakistan as the new nation of Bangladesh.[citation needed]

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- ^ James, Hannah V. A.; Petraglia, Michael D. (2005). "Modern Human Origins and the Evolution of Behavior in the Later Pleistocene Record of South Asia". Current Anthropology. 46 (S5): S3–S27. doi:10.1086/444365. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002B-0DBC-F. ISSN 0011-3204.

- ^ Dennell, R.W.; Rendell, H.; Hailwood, E. (1988). "Early tool-making in Asia: two-million-year-old artefacts in Pakistan". Antiquity. 62 (234): 98–106. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00073555. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ "Oldest human remains found in Pakistan". Rock Art Museum.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh" Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Guide to Archaeology

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. " Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh

- ^ Asrar, Shakeeb. "How British India was divided". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Neelis, Jason (2007), "Passages to India: Śaka and Kuṣāṇa migrations in historical contexts", in Srinivasan, Doris (ed.), On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World, Routledge, pp. 55–94, ISBN 978-90-04-15451-3 Quote: "Numerous passageways through the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan served as migration routes to South Asia from the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppes. Prehistoric and protohistoric exchanges across the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Himalaya ranges demonstrate earlier precedents for routes through the high mountain passes and river valleys in later historical periods. Typological similarities between Northern Neolithic sites in Kashmir and Swat and sites in the Tibetan plateau and northern China show that 'Mountain chains have often integrated rather than isolated peoples.' Ties between the trading post of Shortughai in Badakhshan (northeastern Afghanistan) and the lower Indus valley provide evidence for long-distance commercial networks and 'polymorphous relations' across the Hindu Kush until c. 1800 B.C.' The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) may have functioned as a 'filter' for the introduction of Indo-Iranian languages to the northwestern Indian subcontinent, although routes and chronologies remain hypothetical. (page 55)"

- ^ Marshall, John (2013) [1960], A Guide to Taxila, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–, ISBN 978-1-107-61544-1 Quote: "Here also, in ancient days, was the meeting-place of three great trade-routes, one, from Hindustan and Eastern India, which was to become the `royal highway' described by Megasthenes as running from Pataliputra to the north-west of the Maurya empire; the second from Western Asia through Bactria, Kapisi and Pushkalavati and so across the Indus at Ohind to Taxila; and the third from Kashmir and Central Asia by way of the Srinagar valley and Baramula to Mansehra and so down the Haripur valley. These three trade-routes, which carried the bulk of the traffic passing by land between India and Central and Western Asia, played an all-important part in the history of Taxila. (page 1)"

- ^ Qamar, Raheel; Ayub, Qasim; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Helgason, Agnar; Mazhar, Kehkashan; Mansoor, Atika; Zerjal, Tatiana; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Mehdi, S. Qasim (2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1107–1124. doi:10.1086/339929. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 447589. PMID 11898125.

- ^ Clarkson, Christopher (2014), "East of Eden: Founder Effects and Archaeological Signature of Modern Human Dispersal", in Dennell, Robin; Porr, Martin (eds.), Southern Asia, Australia and the Search for Human Origins, Cambridge University Press, pp. 76–89, ISBN 978-1-107-01785-6 Quote: "The record from South Asia (Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka) has been pivotal in discussions of the archaeological signature of early modern humans east of Africa because of the well-excavated and well-dated sites that have recently been reported in this region and because of the central role South Asia played in early population expansion and dispersals to the east. Genetic studies have revealed that India was the gateway to subsequent colonisation of Asia and Australia and saw the first major population expansion of modern human populations anywhere outside of Africa. South Asia therefore provides a crucial stepping-scone in early modern migration to Southeast Asia and Oceania. (pages 81–2)"

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE, Cambridge University Press Quote: ""Mehrgarh remains one of the key sites in South Asia because it has provided the earliest known undisputed evidence for farming and pastoral communities in the region, and its plant and animal material provide clear evidence for the ongoing manipulation, and domestication, of certain species. Perhaps most importantly in a South Asian context, the role played by zebu makes this a distinctive, localised development, with a character completely different to other parts of the world. Finally, the longevity of the site, and its articulation with the neighbouring site of Nausharo (c. 2800—2000 BCE), provides a very clear continuity from South Asia's first farming villages to the emergence of its first cities (Jarrige, 1984)."

- ^ Fisher, Michael H. (2018), An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-11162-2 Quote: "page 33: "The earliest discovered instance in India of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BCE, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu [Bos indicus] and unhumped [Bos taurus]). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well."

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8, Quote: "(p 29) "The subcontinent's people were hunter-gatherers for many millennia. There were very few of them. Indeed, 10,000 years ago there may only have been a couple of hundred thousand people, living in small, often isolated groups, the descendants of various 'modern' human incomers. Then, perhaps linked to events in Mesopotamia, about 8,500 years ago agriculture emerged in Baluchistan."

- ^ Allchin, Bridget; Allchin, Raymond (1982), The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, p. 131, ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6Quote: "During the second half of the fourth and early part of the third millennium B.C., a new development begins to become apparent in the greater Indus system, which we can now see to be a formative stage underlying the Mature Indus of the middle and late third millennium. This development seems to have involved the whole Indus system, and to a lesser extent the Indo-Iranian borderlands to its west, but largely left untouched the subcontinent east of the Indus system. (page 81)"

- ^ Dales, George; Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark; Alcock, Leslie (1986), Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, p. 4, ISBN 978-0-934718-52-3

- ^ White, David Gordon (2003). Kiss of the Yogini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-226-89483-6.

- ^ India: Reemergence of Urbanization. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ Witzel 1989.

- ^ Kurt A. Behrendt (2007), The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.4—5, 91

- ^ Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a terminus post quem of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).