The word energy derives from Greek ἐνέργεια (energeia), which appears for the first time[when?] in the 4th century BCE works of Aristotle (OUP V, 240, 1991) (including Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics[1] and De Anima).[2]

The modern concept of energy emerged[when?] from the idea of vis viva (living force), which Leibniz defined as the product of the mass of an object and its velocity squared,[full citation needed] he believed that total vis viva was conserved. To account for slowing due to friction, Leibniz claimed that heat consisted of the random motion of the constituent parts of matter — a view described by Bacon in Novum Organon to illustrate inductive reasoning and shared by Isaac Newton, although it would be more than a century until this was generally accepted.

Émilie marquise du Châtelet in her book Institutions de Physique ("Lessons in Physics"), published in 1740, incorporated the idea of Leibniz with practical observations of Gravesande to show that the "quantity of motion" of a moving object is proportional to its mass and its velocity squared (not the velocity itself as Newton taught—what was later called momentum).

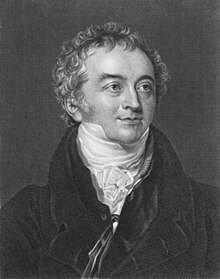

In 1802 lectures to the Royal Society, Thomas Young was the first to use the term energy in its modern sense, instead of vis viva.[3] In the 1807 publication of those lectures, he wrote,

The product of the mass of a body into the square of its velocity may properly be termed its energy.[4]

Gustave-Gaspard Coriolis described "kinetic energy" in 1829 in its modern sense, and in 1853, William Rankine coined the term "potential energy."

It was argued for some years whether energy was a substance (the caloric) or merely a physical quantity.[full citation needed]

- ^ Aristotle, "Nicomachean Ethics", 1098a, at Perseus

- ^ Potentiality and actuality

- ^ Smith, Crosbie (1998). The Science of Energy - a Cultural History of Energy Physics in Victorian Britain. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76420-6.

- ^ Thomas Young (1807). A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts, p. 52.