Human genetic variation is the genetic differences in and among populations. There may be multiple variants of any given gene in the human population (alleles), a situation called polymorphism.

No two humans are genetically identical. Even monozygotic twins (who develop from one zygote) have infrequent genetic differences due to mutations occurring during development and gene copy-number variation.[1] Differences between individuals, even closely related individuals, are the key to techniques such as genetic fingerprinting.

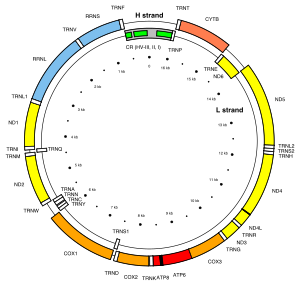

The human genome has a total length of approximately 3.2 billion base pairs (bp) in 46 chromosomes of DNA as well as slightly under 17,000 bp DNA in cellular mitochondria. In 2015, the typical difference between an individual's genome and the reference genome was estimated at 20 million base pairs (or 0.6% of the total).[2] As of 2017, there were a total of 324 million known variants from sequenced human genomes.[3]

Comparatively speaking, humans are a genetically homogeneous species. Although a small number of genetic variants are found more frequently in certain geographic regions or in people with ancestry from those regions, this variation accounts for a small portion (~15%) of human genome variability. The majority of variation exists within the members of each human population. For comparison, rhesus macaques exhibit 2.5-fold greater DNA sequence diversity compared to humans.[4] These rates differ depending on what macromolecules are being analyzed. Chimpanzees have more genetic variance than humans when examining nuclear DNA, but humans have more genetic variance when examining at the level of proteins.[5]

The lack of discontinuities in genetic distances between human populations, absence of discrete branches in the human species, and striking homogeneity of human beings globally, imply that there is no scientific basis for inferring races or subspecies in humans, and for most traits, there is much more variation within populations than between them.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] Despite this, modern genetic studies have found substantial average genetic differences across human populations in traits such as skin colour, bodily dimensions, lactose and starch digestion, high altitude adaptions, drug response, taste receptors, and predisposition to developing particular diseases.[14][12] The greatest diversity is found within and among populations in Africa,[15] and gradually declines with increasing distance from the African continent, consistent with the Out of Africa theory of human origins.[15]

The study of human genetic variation has evolutionary significance and medical applications. It can help scientists reconstruct and understand patterns of past human migration. In medicine, study of human genetic variation may be important because some disease-causing alleles occur more often in certain population groups. For instance, the mutation for sickle-cell anemia is more often found in people with ancestry from certain sub-Saharan African, south European, Arabian, and Indian populations, due to the evolutionary pressure from mosquitos carrying malaria in these regions.

New findings show that each human has on average 60 new mutations compared to their parents.[16][17]

- ^ Bruder CE, Piotrowski A, Gijsbers AA, Andersson R, Erickson S, Diaz de Ståhl T, et al. (March 2008). "Phenotypically concordant and discordant monozygotic twins display different DNA copy-number-variation profiles". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (3): 763–71. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.011. PMC 2427204. PMID 18304490.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

kGP15was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

RefSNPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Xue, Cheng; Raveendran, Muthuswamy; Harris, R. Alan; Fawcett, Gloria L.; Liu, Xiaoming; White, Simon; Dahdouli, Mahmoud; Deiros, David Rio; Below, Jennifer E.; Salerno, William; Cox, Laura (1 December 2016). "The population genomics of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) based on whole-genome sequences". Genome Research. 26 (12): 1651–1662. doi:10.1101/gr.204255.116. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 5131817. PMID 27934697.

- ^ Curnoe, Darren (2003). "Number of ancestral human species: a molecular perspective". HOMO. 53 (3): 208–209. doi:10.1078/0018-442x-00051. PMID 12733395.

- ^ Reich, David (23 March 2018). "Opinion | How Genetics Is Changing Our Understanding of 'Race'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Williams, David R. (1 July 1997). "Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions". Annals of Epidemiology. Special Issue: Interface Between Molecular and Behavioral Epidemiology. 7 (5): 322–333. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00051-3. ISSN 1047-2797. PMID 9250627.

- ^ "1". Race and racism in theory and practice. Berel Lang. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. 2000. ISBN 0-8476-9692-8. OCLC 42389561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Lee, Jun-Ki; Aini, Rahmi Qurota; Sya’bandari, Yustika; Rusmana, Ai Nurlaelasari; Ha, Minsu; Shin, Sein (1 April 2021). "Biological Conceptualization of Race". Science & Education. 30 (2): 293–316. Bibcode:2021Sc&Ed..30..293L. doi:10.1007/s11191-020-00178-8. ISSN 1573-1901. S2CID 231598896.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (4 April 2018). "There's No Scientific Basis for Race—It's a Made-Up Label". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Templeton, Alan Robert (2018). Human Population Genetics and Genomics. London. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-0-12-386026-2. OCLC 1062418886.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Reich, David (2018). Who we are and how we got here: ancient DNA and the new science of the human past (First ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0. OCLC 1006478846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Witherspoon, D. J.; Wooding, S.; Rogers, A. R.; Marchani, E. E.; Watkins, W. S.; Batzer, M. A.; Jorde, L. B. (2007). "Genetic Similarities Within and Between Human Populations". Genetics. 176 (1): 351–359. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.067355. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1893020. PMID 17339205.

- ^ Campbell, Michael (2008). "African Genetic Diversity: Implications for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 9: 403–433. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164258. PMC 2953791. PMID 18593304.

- ^ a b Campbell, Michael C.; Tishkoff, Sarah A. (2008). "AFRICAN GENETIC DIVERSITY: Implications for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 9: 403–433. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164258. ISSN 1527-8204. PMC 2953791. PMID 18593304.

- ^ "We are all mutants: First direct whole-genome measure of human mutation predicts 60 new mutations in each of us". Science Daily. 13 June 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Conrad DF, Keebler JE, DePristo MA, Lindsay SJ, Zhang Y, Casals F, et al. (June 2011). "Variation in genome-wide mutation rates within and between human families". Nature Genetics. 43 (7): 712–4. doi:10.1038/ng.862. PMC 3322360. PMID 21666693.