Ikhshidids الإخشيديون | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 935–969 | |||||||||||

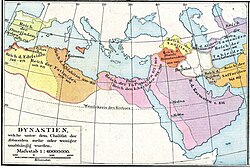

The Ikhshidid state (bright pink) as one of the Abbasid successor states | |||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||||||

| Capital | Fustat | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (predominant) Coptic Western Aramaic Turkic (army) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (predominant) Coptic Orthodox Maronite Church | ||||||||||

| Government | Emirate | ||||||||||

| Wali (governor) | |||||||||||

• 935–946 | Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid | ||||||||||

• 946–961 | Abu'l-Qasim Unujur ibn al-Ikhshid | ||||||||||

• 961–966 | Abu'l-Hasan Ali ibn al-Ikhshid | ||||||||||

• 966–968 | Abu'l-Misk Kafur | ||||||||||

• 968–969 | Abu'l-Fawaris Ahmad ibn Ali ibn al-Ikhshid | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 935 | ||||||||||

| 969 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Ikhshidid dynasty (Arabic: الإخشيديون, ALA-LC: al-Ikhshīdīyūn) was a dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin, who ruled Egypt and the Levant from 935 to 969.[2] The dynasty carried the Arabic title "Wāli" reflecting their position as governors on behalf of the Abbasids. The Ikhshidids came to an end when the Fatimid army conquered Fustat in 969.[3] Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, a Turkic[4][5] mamluk soldier, was appointed governor by the Abbasid Caliph al-Radi.[6]

The Ikhshidid family tomb was in Jerusalem.[7]

- ^ Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Islamic History Through Coins: An Analysis and Catalogue of Tenth-century Ikhshidid Coinage. American Univ in Cairo Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-977-424-930-3.

- ^ Holt, Peter Malcolm (2004). The Crusader States and Their Neighbours, 1098-1291. Pearson Longman. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-582-36931-3.

The two gubernatorial dynasties in Egypt which have already been mentioned, the Tulunids and the Ikhshidids, were both of Mamluk origin.

- ^ The Fatimid Revolution (861-973) and its aftermath in North Africa, Michael Brett, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2 ed. J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 622.

- ^ Abulafia, David (2011). The Mediterranean in History. p. 170.

- ^ Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index. p. 382.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 62.

- ^ Max Van Berchem, MIFAO 44 - Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Part 2 Syrie du Sud T.2 Jérusalem Haram (1927), p13-14 (no.146): “L’émir Muhammad mourut à Damas en 334 (946) et son corps fut transporté et inhumé à Jérusalem. L’émir Unūdjūr mourut en 349 (960) et son corps fut porté à Jérusalem et inhumé à côté de celui de son père. L’émir ‘Ali mourut en 355 (966) et son corps fut transporté à Jérusalem et inhumé à côté de ceux de son père et de son frère. Enfin l'ustādh Kāfūr mourut en 357 (968) et son corps fut transporté et inhumé à Jérusalem, sans doute auprès de ceux de ses maîtres. Ainsi les Ikhshidides avaient leur caveau funéraire à Jérusalem. Bien plus, un auteur contemporain précise que «l'émir Ali fut transporté dans un cercueil à Jérusalem et enterré, avec son frère et son père, ce tout près du Bāb al-asbāt ou porte des Tribus (1). Ce nom désignait et désigne encore la porte du Haram désigne encore la porte du Haram qui s'ouvre dans l'angle nord-est de l'esplanade (2), et précisément derrière le n° 146, à l'intérieur du mur d’enceinte.”

![Coinage of Muhammad al-Ikhshid. Filastin (al-Ramla) mint. Dated AH 332 (943-4 CE).[1] of Ikhshidid dynasty](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Ikhshidids._Muhammad_al-Ikhshid.Filastin_%28al-Ramla%29_mint._Dated_AH_332_%28943-4_CE%29.jpg/270px-Ikhshidids._Muhammad_al-Ikhshid.Filastin_%28al-Ramla%29_mint._Dated_AH_332_%28943-4_CE%29.jpg)