| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, intra-axial hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, cerebral bleed, brain bleed, hemorrhagic stroke |

| |

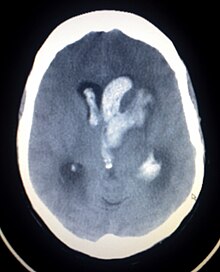

| CT scan of a spontaneous intracerebral bleed, leaking into the lateral ventricles | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Symptoms | Headache, one-sided numbness, weakness, tingling, or paralysis, speech problems, vision or hearing problems, dizziness or lightheadedness or vertigo, nausea/vomiting, seizures, decreased level or total loss of consciousness, neck stiffness, memory loss, attention and coordination problems, balance problems, fever, shortness of breath (when bleed is in the brain stem) [1][2] |

| Complications | Coma, persistent vegetative state, cardiac arrest (when bleeding is severe or in the brain stem), death |

| Causes | Brain trauma, aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, brain tumors, hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke[1] |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, amyloidosis, alcoholism, low cholesterol, blood thinners, cocaine use[2] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Ischemic stroke[1] |

| Treatment | Blood pressure control, surgery, ventricular drain[1] |

| Prognosis | 20% good outcome[2] |

| Frequency | 2.5 per 10,000 people a year[2] |

| Deaths | 44% die within one month[2] |

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as hemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain (i.e. the parenchyma), into its ventricles, or into both.[3][4][1] An ICH is a type of bleeding within the skull and one kind of stroke (ischemic stroke being the other).[3][4] Symptoms can vary dramatically depending on the severity (how much blood), acuity (over what timeframe), and location (anatomically) but can include headache, one-sided weakness, numbness, tingling, or paralysis, speech problems, vision or hearing problems, memory loss, attention problems, coordination problems, balance problems, dizziness or lightheadedness or vertigo, nausea/vomiting, seizures, decreased level of consciousness or total loss of consciousness, neck stiffness, and fever.[2][1]

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur on the background of alterations to the blood vessels in the brain, such as cerebral arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, brain trauma, brain tumors and an intracranial aneurysm, which can cause intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[1]

The biggest risk factors for spontaneous bleeding are high blood pressure and amyloidosis.[2] Other risk factors include alcoholism, low cholesterol, blood thinners, and cocaine use.[2] Diagnosis is typically by CT scan.[1]

Treatment should typically be carried out in an intensive care unit due to strict blood pressure goals and frequent use of both pressors and antihypertensive agents.[1][5] Anticoagulation should be reversed if possible and blood sugar kept in the normal range.[1] A procedure to place an external ventricular drain may be used to treat hydrocephalus or increased intracranial pressure, however, the use of corticosteroids is frequently avoided.[1] Sometimes surgery to directly remove the blood can be therapeutic.[1]

Cerebral bleeding affects about 2.5 per 10,000 people each year.[2] It occurs more often in males and older people.[2] About 44% of those affected die within a month.[2] A good outcome occurs in about 20% of those affected.[2] Intracerebral hemorrhage, a type of hemorrhagic stroke, was first distinguished from ischemic strokes due to insufficient blood flow, so called "leaks and plugs", in 1823.[6]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, et al. (Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing) (July 2015). "Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association". Stroke. 46 (7): 2032–2060. doi:10.1161/str.0000000000000069. PMID 26022637.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Caceres JA, Goldstein JN (August 2012). "Intracranial hemorrhage". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 30 (3): 771–794. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.003. PMC 3443867. PMID 22974648.

- ^ a b "Brain Bleed/Hemorrhage (Intracranial Hemorrhage): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment".

- ^ a b Naidich TP, Castillo M, Cha S, Smirniotopoulos JG (2012). Imaging of the Brain, Expert Radiology Series,1: Imaging of the Brain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 387. ISBN 978-1416050094. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.

- ^ Ko SB, Yoon BW (December 2017). "Blood Pressure Management for Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: The Evidence". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 38 (6): 718–725. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1608777. PMID 29262429.

- ^ Hennerici M (2003). Imaging in Stroke. Remedica. p. 1. ISBN 9781901346251. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.