| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

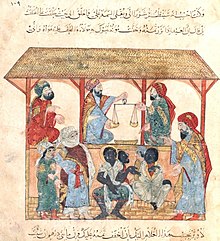

Islamic views on slavery represent a complex and multifaceted body of Islamic thought,[1][2] with various Islamic groups or thinkers espousing views on the matter which have been radically different throughout history.[3] Slavery was a mainstay of life in pre-Islamic Arabia and surrounding lands.[1][4] The Quran and the hadith (sayings of Muhammad) address slavery extensively, assuming its existence as part of society but viewing it as an exceptional condition and restricting its scope.[4] Early Islam forbade enslavement of dhimmis, the free members of Islamic society, including non-Muslims and set out to regulate and improve the conditions of human bondage. Islamic law regarded as legal slaves only those non-Muslims who were imprisoned or bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity.[4] In later classical Islamic law, the topic of slavery is covered at great length.[3]

Slavery in Islamic law is not based on race or ethnicity. However, while there was no legal distinction between white European and black African slaves, in some Muslim societies they were employed in different roles.[5] Slaves in Islam were mostly assigned to the service sector, including as concubines, cooks, and porters.[6] There were also those who were trained militarily, converted to Islam, and manumitted to serve as soldiers; this was the case with the Mamluks, who later managed to seize power by overthrowing their Muslim masters, the Ayyubids.[7][8] In some cases, the harsh treatment of slaves also led to notable uprisings, such as the Zanj Rebellion.[9] "The Caliphate in Baghdad at the beginning of the 10th Century had 7,000 black eunuchs and 4,000 white eunuchs in his palace."[10][page needed] The Arab slave trade typically dealt in the sale of castrated male slaves. Black boys at the age of eight to twelve had their penises and scrota completely amputated. Reportedly, about two out of three boys died, but those who survived drew high prices.[11] However, according to Islamic law and Muslim jurists castration of slaves was deemed unlawful this view is also mentioned in the Hadith.[12][13] Bernard Lewis opines that in later times, the domestic slaves, although subjected to appalling privations from the time of their capture until their final destination, seemed to be treated reasonably well once they were placed in a family and to some extent accepted as members of the household.[14]

The hadiths, which differ between Shia and Sunni,[15] address slavery extensively, assuming its existence as part of society but viewing it as an exceptional condition and restricting its scope.[16][17] The hadiths forbade enslavement of dhimmis, the non-Muslims of Islamic society, and Muslims. They also regarded slaves as legal only when they were non-Muslims who were imprisoned, bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity.[17]

The Muslim slave trade was most active in West Asia, Eastern Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[20] After the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had been suppressed, the ancient Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade and the Red Sea slave trade continued to traffic slaves from the African continent to the Middle East.[20] Estimates vary widely, with some suggesting up to 17 million slaves to the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa.[21] Abolitionist movements began to grow during the 19th century, prompted by both Muslim reformers and diplomatic pressure from Britain. The first Muslim country to prohibit slavery was Tunisia, in 1846.[22] During the 19th and early 20th centuries all large Muslim countries, whether independent or under colonial rule, banned the slave trade and/or slavery. The Dutch East Indies abolished slavery in 1860 but effectively ended in 1910, while British India abolished slavery in 1862.[23] The Ottoman Empire banned the African slave trade in 1857 and the Circassian slave trade in 1908,[24] while Egypt abolished slavery in 1895, Afghanistan in 1921 and Persia in 1929.[25] In some Muslim countries in the Arabian peninsula and Africa, slavery was abolished in the second half of the 20th century: 1962 in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Oman in 1970, Mauritania in 1981.[26] However, slavery has been documented in recent years, despite its illegality, in Muslim-majority countries in Africa including Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Mali, and Sudan.[27][28]

One notable example is Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, who is noted for being the first Muezzin.[29] In modern times, various Muslim organizations reject the permissibility of slavery and it has since been abolished by all Muslim majority countries.[30] With abolition of slavery in the Muslim world, the practice of slavery came to an end.[31] Many modern Muslims see slavery as contrary to Islamic principles of justice and equality, however, Islam had a different system of slavery, that involved many intricate rules on how to handle slaves.[32][33] However, there are Islamic extremist groups and terrorist organizations who have revived the practice of slavery while they were active.[34]

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E., “Slaves and Slavery”, in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- ^ Brunschvig, R., “ʿAbd”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ a b Lewis 1994, Ch.1 Archived 2001-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Dror Ze’evi (2009). "Slavery". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-02-23. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ^ Jane Hathaway, The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem, Cambridge University Press, 2018 ISBN 9781107108295

- ^ Segal 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 98-99.

- ^ Lapidus 2014, p. 195.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Segal 2002.

- ^ Wilson, Jean D.; Roehrborn, Claus (1999). "Long-Term Consequences of Castration in Men: Lessons from the Skoptzy and the Eunuchs of the Chinese and Ottoman Courts". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 84 (12): 4324–4331. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.12.6206. PMID 10599682.

- ^ https://boris.unibe.ch/186051/1/Naming_eunuchs_BCDSS.pdf

- ^ https://sunnah.com/nasai:4736

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 13–14.

- ^ "Development of History and Hadith Collections". www.al-islam.org. 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Sahih Bukhari | Chapter: 48 | Manumission of Slaves". ahadith.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ a b "BBC - Religions - Islam: Slavery in Islam". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ Jonathan E. Brockopp (2000), Early Mālikī Law: Ibn ʻAbd Al-Ḥakam and His Major Compendium of Jurisprudence, Brill, ISBN 978-9004116283, pp. 131

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 77

- ^ a b La Rue, George M. (17 August 2023). "Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199846733-0051. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Focus on the slave trade". May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Montana, Ismael (2013). The Abolition of Slavery in Ottoman Tunisia. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813044828.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Erdem, Y. Hakan (1996). Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its Demise, 1800-1909. Macmillan. pp. 95–151. ISBN 0333643232.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 110–116.

- ^ Martin A. Klein (2002), Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition, Page xxii, ISBN 0810841029

- ^ Segal, page 206. See later in article.

- ^ Segal, page 222. See later in article.

- ^ Robinson, David (2004-01-12). Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53366-9.

- ^ "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library". 2018-11-03. Archived from the original on 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Cortese 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

eoqwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ali 2006, pp. 53–54: "...the practical limitations of the Prophet’s mission meant that acquiescence to slave ownership was necessary, though distasteful, but meant to be temporary."

- ^ "ISIS and Their Use of Slavery". International Centre for Counter-Terrorism - ICCT. Retrieved 2024-08-30.