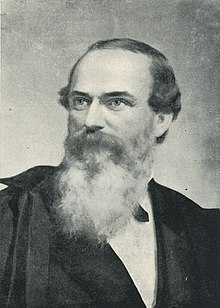

James S. Rollins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 3, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas L. Anderson |

| Succeeded by | George W. Anderson |

| Constituency | 2nd district (1861–63) 9th district (1863–65) |

| Member of the Missouri Legislature | |

| In office 1838 1840 1854 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 19, 1812 Richmond, Kentucky |

| Died | January 9, 1888 (aged 75) Columbia, Missouri |

| Political party | Whig (1836–1855) Know-Nothing 1855–1860 Constitutional Union (1860–61) Union (1861–64) Democratic (1864–78) Republican (after 1878) |

| Spouse | Mary Elizabeth Rollins |

| Signature | |

James Sidney Rollins (April 19, 1812 – January 9, 1888) was a 19th century Missouri politician and lawyer. He helped establish the University of Missouri at Columbia, and led the successful effort to get it located in Boone County, and gained funding for the proposed state university with the passage of a series of legislative acts in the General Assembly of Missouri (state legislature) at the Missouri State Capitol in the state capital town of Jefferson City. For his efforts, he was named "Father of the University of Missouri."[1]

As a border state United States Representative (Congressman), in the lower chamber of the United States House of Representatives, with member Rollins played a role in the Congress of the United States's passage and ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, abolishing slavery in 1865. He changed his vote to support the proposed constitutional amendment, and spoke in favor of it on the floor of the House Chamber at the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.. Representative Rollins was a member of the old [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party] in the 1830s and 1840s for the first 20 years of his political career. When that divided political party broke up in the beginning of the 1850s, he began a political transition, changing parties and affiliations several times before eventually settling to becoming a Republican late in his life. Rollins' lifelong support of capitalism and business development was compatible with initial Republican economic policies, but his situation as a major slaveowner prevented him from joining the Republican Party until well after the American Civil War (1861-1865).[2]