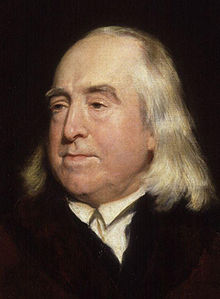

Jeremy Bentham | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Bentham by Henry William Pickersgill | |

| Born | 15 February 1748 [O.S. 4 February 1747/8] London, England |

| Died | 6 June 1832 (aged 84) London, England |

| Education | The Queen's College, Oxford (MA) |

| Era | |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Utilitarianism Legal positivism Liberalism Radicalism Epicureanism |

| Academic career | |

| Influences | |

Main interests | Political philosophy, philosophy of law, ethics, economics |

Notable ideas | Principle of utility Felicific calculus |

| Signature | |

| |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Radicalism |

|---|

Jeremy Bentham (/ˈbɛnθəm/; 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.] – 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.[1][2][3][4][5]

Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong."[6][7] He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and (in an unpublished essay) the decriminalising of homosexual acts.[8][9] He called for the abolition of slavery, capital punishment, and physical punishment, including that of children.[10][failed verification] He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights.[11][12][13][14] Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts".[3][15] However, he viewed the Magna Carta as important, citing it to argue that the treatment of convicts in Australia was unlawful. Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fictions.

Bentham's students included his secretary and collaborator James Mill, the latter's son, John Stuart Mill, the legal philosopher John Austin and American writer and activist John Neal. He "had considerable influence on the reform of prisons, schools, poor laws, law courts, and Parliament itself."[16]

On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected and then to be permanently preserved as an "auto-icon" (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display in the entrance of the Student Centre at University College London (UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the "spiritual founder" of UCL. However, he played only a limited direct part in its foundation.[17]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ODNBwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Johnson2012was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Sweetwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Sprigge, Timothy L. S., ed. (2017) [1968]. The Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham: Volume I: 1752–76 (PDF). London: UCL Press. pp. xxvii, l, 294. ISBN 978-1-911576-05-1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

utilitarianphilosophy.comwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bentham, Jeremy. A Comment on the Commentaries and a Fragment on Government, edited by J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart. London: The Athlone Press. 1977. p. 393.

- ^ Burns 2005, pp. 46–61.

- ^ Bentham 2008, pp. 389–406.

- ^ Campos Boralevi 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Bedau 1983, pp. 1033–1065.

- ^ Sunstein 2004, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Francione 2004, p. 139: footnote 78

- ^ Gruen 2003.

- ^ Benthall 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Harrison 1995, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Roberts, Roberts & Bisson 2016, p. 307.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

UCL Academic Figureswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).