| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

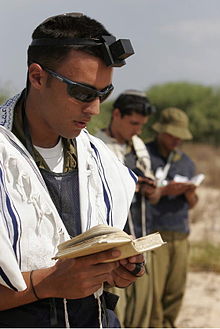

Jewish prayer (Hebrew: תְּפִילָּה, tefilla [tfiˈla]; plural תְּפִילּוֹת tefillot [tfiˈlot]; Yiddish: תּפֿלה, romanized: tfile [ˈtfɪlə], plural תּפֿלות tfilles [ˈtfɪləs]; Yinglish: davening /ˈdɑːvənɪŋ/ from Yiddish דאַוון davn 'pray') is the prayer recitation that forms part of the observance of Rabbinic Judaism. These prayers, often with instructions and commentary, are found in the Siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book.

Prayer, as a "service of the heart," is in principle a Torah-based commandment.[1] It is mandatory for Jewish women and men.[2] However, the rabbinic requirement to recite a specific prayer text does differentiate between men and women: Jewish men are obligated to recite three prayers each day within specific time ranges (zmanim), while, according to many approaches, women are only required to pray once or twice a day, and may not be required to recite a specific text.[3]

Traditionally, three prayer services are recited daily:

- Morning prayer: Shacharit or Shaharit (שַחֲרִית, "of the dawn")

- Afternoon prayer: Mincha or Minha (מִנְחָה), named for the flour offering that accompanied sacrifices at the Temple in Jerusalem,

- Evening prayer:[4] Arvit (עַרְבִית, "of the evening") or Maariv (מַעֲרִיב, "bringing on night")

Two additional services are recited on Shabbat and holidays:

- Musaf (מוּסָף, "additional") are recited by Orthodox and Conservative congregations on Shabbat, major Jewish holidays (including Chol HaMoed), and Rosh Chodesh.

- Ne'ila (נְעִילָה, "closing"), was traditionally recited on communal fast days and is now recited only on Yom Kippur.

A distinction is made between individual prayer and communal prayer, which requires a quorum known as a minyan, with communal prayer being preferable as it permits the inclusion of prayers that otherwise would be omitted.

According to tradition, many of the current standard prayers were composed by the sages of the Great Assembly in the early Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). The language of the prayers, while clearly from this period, often employs biblical idiom. The main structure of the modern prayer service was fixed in the Tannaic era (1st–2nd centuries CE), with some additions and the exact text of blessings coming later. Jewish prayerbooks emerged during the early Middle Ages during the period of the Geonim of Babylonia (6th–11th centuries CE).[5]

Over the last 2000 years, traditional variations have emerged among the traditional liturgical customs of different Jewish communities, such as Ashkenazic, Sephardic, Yemenite, Eretz Yisrael and others, or rather recent liturgical inventions such as Nusach Sefard and Nusach Ari. However the differences are minor compared with the commonalities. Most of the Jewish liturgy is sung or chanted with traditional melodies or trope. Synagogues may designate or employ a professional or lay hazzan (cantor) for the purpose of leading the congregation in prayer, especially on Shabbat or holy holidays.

- ^ Tractate Ta’anit 2a

- ^ Steinsaltz, Adin (2000). A guide to Jewish prayer (1st American paperback ed.). New York: Schocken Books. pp. 26ff. ISBN 978-0805211474. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Bar-Hayim, David (Rabbi, Posek). "Women and Davening: Shemone Esre, Keriyath Shem". machonshilo.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weinreb, Tzvi Hersh; Berger, Shalom Z.; Schreier, Joshua, eds. (2012). [Talmud Bavli] = Koren Talmud Bavli. Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), Adin (1st Hebrew/English ed.). Jerusalem: Shefa Foundation. p. 176. ISBN 9789653015630. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Center for Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania. "Jewish Liturgy: The Siddur and the Mahzor". Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2009.