John Lewis | |

|---|---|

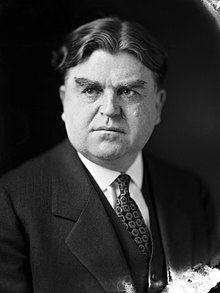

Lewis, c. 1927 | |

| 9th President of the United Mine Workers | |

| In office 1919–1960 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Kennedy |

| 1st President of the Congress of Industrial Organizations | |

| In office 1936–1940 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Philip Murray |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Llewellyn Lewis February 12, 1880 Cleveland, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 1969 (aged 89) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Ridge Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Myrta Bell

(m. 1907; died 1942) |

| Children | 3 |

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the history of coal mining, he was the driving force behind the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which established the United Steel Workers of America and helped organize millions of other industrial workers in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. After resigning as head of the CIO in 1941, thus keeping his promise of resignation if President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1940 election against Wendell Willkie, Lewis took the United Mine Workers out of the CIO in 1942 and in 1944 took the union into the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Lewis was a Republican but played a major role in helping Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt win a landslide victory for the US presidency in 1936. He was an isolationist, and broke with Roosevelt in 1940 on FDR's anti-Nazi foreign policy. Lewis was an effective, aggressive fighter and strike leader who gained high wages for his membership while steamrolling over his opponents, including the United States government. Lewis was one of the most controversial and innovative leaders in the history of labor, gaining credit for building the industrial unions of the CIO into a political and economic powerhouse to rival the AFL. During World War II, he was widely criticized by calling nationwide coal strikes, which critics believed to be damaging to the American economy and war effort.

His massive leonine head, forest-like eyebrows, firmly set jaw, powerful voice, and ever-present scowl thrilled his supporters, angered his enemies, and delighted cartoonists. Coal miners for 40 years hailed him as their leader, whom they credited with bringing high wages, pensions and medical benefits.[1] After his successor died shortly after taking office, Lewis hand-picked Tony Boyle, a miner from Montana, to take the presidency of the union in 1963.

- ^ Robert H. Zieger. "Lewis, John L." American National Biography Online Feb. 2000 Archived 2017-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "LABOR: Horatius & the Great Ham". TIME. December 16, 1946. Archived from the original on November 11, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2013.(subscription required)