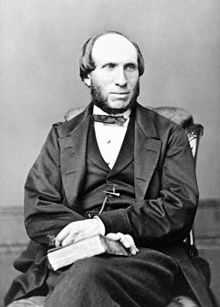

John Struthers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 February 1823 Brucefield, Dunfermline |

| Died | 24 February 1899 (aged 76) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Resting place | Warriston Cemetery |

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation(s) | Anatomist, professor |

| Employer(s) | U. Edinburgh, U. Aberdeen |

| Spouse | Christina Margaret Alexander |

| Children | Three sons, four daughters |

| Parent(s) | Alexander, Mary (Reid) |

Sir John Struthers MD FRCSE FRSE (21 February 1823 – 24 February 1899) was the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen. He was a dynamic teacher and administrator, transforming the status of the institutions in which he worked. He was equally passionate about anatomy, enthusiastically seeking out and dissecting the largest and finest specimens, including whales, and troubling his colleagues with his single-minded quest for money and space for his collection. His collection was donated to Surgeon's Hall in Edinburgh.[1]

Among scientists, he is perhaps best known for his work on the ligament which bears his name. His work on the rare and vestigial ligament of Struthers came to the attention of Charles Darwin, who used it in his Descent of Man to help argue the case that man and other mammals shared a common ancestor ; or "community of descent," as Darwin expressed it.

Among the public, Struthers was famous for his dissection of the "Tay Whale", a humpback whale that appeared in the Firth of Tay, was hunted and then dragged ashore to be exhibited across Britain. Struthers took every opportunity he could to dissect it and recover its bones, and eventually wrote a monograph on it.

In the medical profession, he was known for transforming the teaching of anatomy, for the papers and books that he wrote, as well as for his efficient work in his medical school, for which he was successively awarded medicine's highest honours, including membership of the General Medical Council, fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the presidency of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, and finally a knighthood.

- ^ "Key Object Page | Frog Skeleton". Surgeon's Hall Museums.

It is part of a collection of comparative anatomy put together by John Struthers (1823–1899), Scottish zoologist and anatomist. At one time, the museum held a whole array of animals, from a tiger skeleton and a dolphin skull, to the pulmonary vein of a whale and the skin of a porcupine fish. Much of what we do have will be featured in the new displays that open in September.