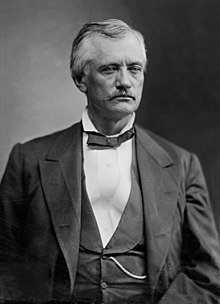

John T. Morgan | |

|---|---|

Morgan in 1877 | |

| United States Senator from Alabama | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – June 11, 1907 | |

| Preceded by | George Goldthwaite |

| Succeeded by | John H. Bankhead |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Tyler Morgan June 20, 1824 Athens, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 1907 (aged 82) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

John Tyler Morgan (June 20, 1824 – June 11, 1907) was an American politician who was a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War and later was elected for six terms as the U.S. Senator (1877–1907) from the state of Alabama.[1] A prominent slaveholder before the Civil War,[2] he became the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama during the Reconstruction era.[3][4][5][6] Morgan and fellow Klan member Edmund W. Pettus became the ringleaders of white supremacy in Alabama and did more than anyone else in the state to overthrow Reconstruction efforts in the wake of the Civil War.[7][8] When President Ulysses S. Grant dispatched U.S. Attorney General Amos Akerman to prosecute the Klan under the Enforcement Acts, Morgan was arrested and jailed.[9]

Due to his notoriety in Alabama for opposing Reconstruction efforts,[10] Morgan was elected as a U.S. Senator in 1876.[11] During his subsequent six terms as Senator, he was an outspoken proponent of black disfranchisement, racial segregation, and lynching African-Americans.[12] According to historians, he played a leading role "in forging the ideology of white supremacy that dominated American race relations from the 1890s to the 1960s."[13] Widely considered to be among the most notorious racist ideologues of his time, he is often credited by scholars with laying the foundation of the Jim Crow era.[14]

In addition to his lifelong efforts to uphold white supremacy,[15] Morgan became an ardent expansionist and imperialist during the Gilded Age.[16] He envisioned the United States as a globe-spanning empire and believed that island nations such as Hawaii and the Philippines should be forcibly annexed in order for the country to dominate trade in the Pacific Ocean. Accordingly, he advocated for the United States to annex the independent Republic of Hawaii and to construct an inter-oceanic canal in Central America.[17] Due to this advocacy, he was often posthumously referred to as "the Father of the Panama Canal"[18] despite being a proponent of the Canal to be located in Nicaragua. Morgan was a staunch opponent of women's suffrage.[19]

After his death by heart attack in 1907,[20] Morgan's numerous relatives remained influential in Alabama politics and high society for many decades. His extended family owned the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery.[21] His nephew and protege, Anthony Dickinson Sayre, was President of the Alabama State Senate and later an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama.[22] Sayre played a pivotal role in passing the landmark 1893 Sayre Act which disenfranchised black Alabamians for seventy years and ushered in the Jim Crow period in the state.[23][24] Morgan's grand-niece was Jazz Age socialite Zelda Sayre, the wife of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald.[21]

- ^ The Selma Times-Journal 1925, p. 8.

- ^ National Archives 2016; White & Langer 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Davis 1924was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bowers 1929was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

The Montgomery Advertiser 1960was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hauser 2022; Svrluga 2016; Hebert 2010; Holthouse 2008.

- ^ 60th United States Congress 1908, pp. 155, 189, 192.

- ^ Hebert 2010; Holthouse 2008.

- ^ Bowers 1929, p. 430; The Montgomery Advertiser 1960, p. 4.

- ^ 60th United States Congress 1908, pp. 189, 192.

- ^ Fry 1992, p. 37.

- ^ Svrluga 2016; Hebert 2010; Holthouse 2008.

- ^ Upchurch 2004.

- ^ Upchurch 2004; Holthouse 2008.

- ^ Jones 1928, p. 49; Holthouse 2008.

- ^ White & Langer 2015.

- ^ Fry 1985, pp. 329–346.

- ^ Spradling 1925, p. 16.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fry 1992, p. 257.

- ^ a b Milford 1970, p. 5.

- ^ Alabama Register 1915, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Levitsky & Ziblatt 2018, p. 111; Kousser 1974, pp. 134–137.

- ^ Lanahan 1996, p. 444; Warren 2011.