Josef Albers | |

|---|---|

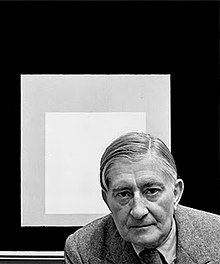

Albers in front of one of his Homage to the Square paintings | |

| Born | March 19, 1888 |

| Died | March 25, 1976 (aged 88) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Education | Königliche Kunstschule zu Berlin, Königliche Bayerische Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, Bauhaus |

| Known for | Abstract painting, study of color |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Geometric abstraction |

| Spouse | |

| Website | https://albersfoundation.org/ |

Josef Albers (/ˈælbərz, ˈɑːl-/; German: [ˈalbɐs]; March 19, 1888 – March 25, 1976) was a German-born American artist and educator who is considered one of the most influential 20th-century art teachers in the United States.[1][2] Born in 1888 in Bottrop, Westphalia, Germany, into a Roman Catholic family with a background in craftsmanship, Albers received practical training in diverse skills like engraving glass, plumbing, and wiring during his childhood. He later worked as a schoolteacher from 1908 to 1913 and received his first public commission in 1918 and moved to Munich in 1919.

In 1920, Albers joined the Weimar Bauhaus as a student and became a faculty member in 1922, teaching the principles of handicrafts. With the Bauhaus's move to Dessau in 1925, he was promoted to professor and married Anni Albers, a student at the institution and a textile artist. Albers' work in Dessau included designing furniture and working with glass, collaborating with established artists like Paul Klee. Following the Bauhaus's closure under Nazi pressure in 1933, Albers emigrated to the United States. He was appointed as the head of the painting program at the experimental liberal arts institution Black Mountain College in North Carolina, a position he held until 1949.

At Black Mountain, Albers taught students who would later go on to become prominent artists such as Ruth Asawa and Robert Rauschenberg, and invited contemporary American artists to teach in the summer seminar, including the choreographer Merce Cunningham and Harlem Renaissance painter Jacob Lawrence. In 1950, he left for Yale University to head the design department, contributing significantly to its graphic design program. Albers' teaching methodology, prioritizing practical experience and vision in design, had a profound impact on the development of postwar Western visual art, while his book Interaction of Color, published in 1963, is considered a seminal work on color theory.[3]

In addition to being a teacher, Albers was an active abstract painter and theorist, best known for his series Homage to the Square, in which he explored chromatic interactions with nested squares, meticulously recording the colors used. He also created murals, such as those for the Corning Glass Building and the Time & Life Building in New York City. In 1970, he and his wife lived in Orange, Connecticut, where they continued to work in their private studio. In 1971, Albers was first living artist to be given a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[4] Albers died in his sleep on March 25, 1976, at the Yale New Haven Hospital after being admitted for a possible heart ailment.

- ^ "Josef Albers, Artist and Teacher, Dies". The New York Times. March 26, 1976. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

As a teacher and theoretician as well as a painter, Mr. Albers had a wide influence on several generations of artists [in the United States] and abroad.

- ^ Upshaw, Reagan (November 29, 2018). "A portrait of Josef Albers, in all his originality". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

[Albers] would become arguably the most influential art teacher in 20th-century America.

- ^ Heller, Steven (January 22, 2015). "When Bauhaus Met Lounge Music". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

[Albers] had a profound influence on the theory and practice of art and design—through his influential book 'Interaction of Color', but also in his classes at Black Mountain College, where he was the head of the art department, and Yale University, where he oversaw the department of design through an overhaul in curriculum in favor of rigorous exercises and an emphasis on detail.

- ^ Crichton-Miller, Emma (November 11, 2016). "Celebrating Bauhaus artists Josef and Anni Albers". Financial Times. Retrieved November 25, 2023.