37°49′30″N 40°32′24″E / 37.825°N 40.54°E

| Kurkh Monoliths | |

|---|---|

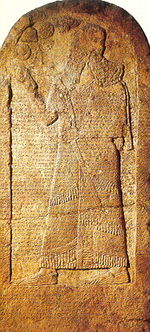

The Monolith stele of Shalmaneser III | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Size | 2.2m & 1.93m |

| Writing | Akkadian cuneiform |

| Created | c. 852 BC & 879 BC |

| Discovered | Üçtepe Höyük, 1861 |

| Present location | British Museum |

| Identification | ME 118883 and ME 118884 |

The Kurkh Monoliths are two Assyrian stelae of c. 852 BC and 879 BC that contain a description of the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II and his son Shalmaneser III. The Monoliths were discovered in 1861 by a British archaeologist John George Taylor, who was the British Consul-General stationed in the Ottoman Eyalet of Kurdistan, at a site called Kurkh, which is now known Üçtepe Höyük, in the district of Bismil, in the province of Diyarbakir of Turkey. Both stelae were donated by Taylor to the British Museum in 1863.[1]

The Shalmaneser III monolith contains a description of the Battle of Qarqar at the end. This description contains the name "A-ha-ab-bu Sir-ila-a-a" which is generally accepted to be a reference to Ahab, king of Israel;[2][3] although this is the only reference to the term "Israel" in Assyrian and Babylonian records, which usually refer to the Northern Kingdom as the "House of Omri" in reference to its ruling dynasty—a fact brought up by some scholars who dispute the proposed translation.[4][5] It is also one of four known contemporary inscriptions containing the name of Israel, the others being the Merneptah Stele, the Tel Dan Stele, and the Mesha Stele.[6][7][8] This description is also the oldest document that mentions the Arabs.[9]

According to the inscription Ahab committed a force of 2,000 chariots and 10,000 foot soldiers to the coalition against Assyria.[10]

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship edited by Frederick E. Greenspahn, NYU Press, 2008 P.11

- ^ Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives By Jonathan Michael Golden, ABC-CLIO, 2004, P.275

- ^ Israel in Transition 2: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIA, edited by Lester L. Grabbe, p56, quote "The single case where "Israel" is mentioned is Shalmaneser's account of his battle with the coalition at Qarqar"

- ^ Kelle 2002, p. 642: "The question of the identity of a-ha-ab-bu involves the fact that the other Assyrian inscriptions for 853-852 do not mention this person as a leader or participant in the coalition. They mention only Adad-idri and Irhuleni (see Bull Inscription and Black Obelisk). This lack of any further references leads some writers to assert that one should not equate the reference on the Monolith Inscription with Ahab of Israel. For example, W. Gugler supports A. S. van der Woude's thesis that tile inscription simply refers to an unknown northwest Syrian ruler. [Footnote:] W. Gugler, Jehu und seine Revolution (Kampen: Kok Pharos, 1996), 70-77. Some earlier readings also suggested "Ahab of Jezreel" (see Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia [ed. H. Rawlinson; 5 vols.: London: British Museum, 1861-1909], 3:6). However, this no longer appears to be considered, and the mot recent studies do not mention it (e.g., Grayson, Assyrian Rulers, 11-24)."

- ^ Lemche 1998, pp. 46, 62: "No other inscription from Palestine, or from Transjordan in the Iron Age, has so far provided any specific reference to Israel. ... The name of Israel was found in only a very limited number of inscriptions, one from Egypt, another separated by at least 250 years from the first, in Transjordan. A third reference is found in the stele from Tel Dan—if it is genuine, a question not yet settled. The Assyrian and Mesopotamian sources only once mentioned a king of Israel, Ahab, in a spurious rendering of the name."

- ^ Maeir, Aren. "Maeir, A. M. 2013. Israel and Judah. Pp. 3523–27 in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. New York: Blackwell".

The earliest certain mention of the ethnonym Israel occurs in a victory inscription of the Egyptian king MERENPTAH, his well-known "Israel Stela" (ca. 1210 BCE); recently, a possible earlier reference has been identified in a text from the reign of Rameses II (see RAMESES I–XI). Thereafter, no reference to either Judah or Israel appears until the ninth century. The pharaoh Sheshonq I (biblical Shishak; see SHESHONQ I–VI) mentions neither entity by name in the inscription recording his campaign in the southern Levant during the late tenth century. In the ninth century, Israelite kings, and possibly a Judaean king, are mentioned in several sources: the Aramaean stele from Tel Dan, inscriptions of SHALMANESER III of Assyria, and the stela of Mesha of Moab. From the early eighth century onward, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah are both mentioned somewhat regularly in Assyrian and subsequently Babylonian sources, and from this point on there is relatively good agreement between the biblical accounts on the one hand and the archaeological evidence and extra-biblical texts on the other.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ FLEMING, DANIEL E. (1998-01-01). "Mari and the Possibilities of Biblical Memory". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 92 (1): 41–78. JSTOR 23282083.

The Assyrian royal annals, along with the Mesha and Dan inscriptions, show a thriving northern state called Israël in the mid—9th century, and the continuity of settlement back to the early Iron Age suggests that the establishment of a sedentary identity should be associated with this population, whatever their origin. In the mid—14th century, the Amarna letters mention no Israël, nor any of the biblical tribes, while the Merneptah stele places someone called Israël in hill-country Palestine toward the end of the Late Bronze Age. The language and material culture of emergent Israël show strong local continuity, in contrast to the distinctly foreign character of early Philistine material culture.

- ^ The Ancient Arabs: Nomads on the Borders of the Fertile Crescent, 9th–5th Centuries B.C., p. 75

- ^ Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography edited by Ada Cohen, Steven E. Kangas P:126