| Kwashiorkor | |

|---|---|

| |

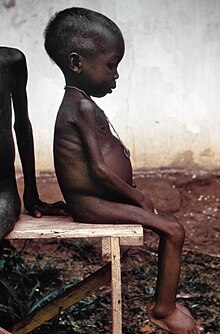

| A young girl with kwashiorkor in a relief camp during the Nigerian Civil War | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Kwashiorkor (/ˌkwɒʃiˈɔːrkɔːr, -kər/ KWOSH-ee-OR-kor, -kər, is also KWASH-)[1] is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates.[2] It is thought to be caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption (or lack of good quality protein), which distinguishes it from marasmus. Recent studies have found that a lack of antioxidant micronutrients such as β-carotene, lycopene, other carotenoids, and vitamin C as well as the presence of aflatoxins may play a role in the development of the disease.[3] However, the exact cause of Kwashiorkor is still unknown. Inadequate food supply is correlated with occurrences of kwashiorkor; occurrences in high income countries are rare.[4] It occurs amongst weaning children to ages of about five years old.[2]

Conditions analogous to kwashiorkor were well documented around the world throughout history.[5] However, Jamaican pediatrician Cicely Williams introduced the term in 1935, two years after she published the disease's first formal description. Williams was the first to conduct research on kwashiorkor and differentiate it from other dietary deficiencies. She was the first to suggest that this might be a deficiency of protein.[6][7] The name is derived from the Ga language of coastal Ghana, translated as "the sickness the baby gets when the new baby comes" or "the disease of the deposed child", and reflecting the development of the condition in an older child who has been weaned from the breast when a younger sibling comes.[8] Breast milk contains amino acids vital to a child's growth. In at-risk populations, kwashiorkor may develop after children are weaned from breast milk and begin consuming a diet high in carbohydrates, including maize, cassava or rice.[2][6]

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Benjamin & Lappin Kwashiorkorwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pham, Thi-Phuong-Thao; Alou, Maryam Tidjani; Golden, Michael H.; Million, Matthieu; Raoult, Didier (January 2021). "Difference between kwashiorkor and marasmus: Comparative meta-analysis of pathogenic characteristics and implications for treatment". Microbial Pathogenesis. 150: 104702. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104702. PMID 33359074. S2CID 229694345. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Liu T, Howard RM, Mancini AJ, Weston WL, Paller AS, Drolet BA, et al. (2001). "Kwashiorkor in the United States: fad diets, perceived and true milk allergy, and nutritional ignorance". Archives of Dermatology. 137 (5): 630–6. PMID 11346341.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nott, John (May 2021). "'No one may starve in the British Empire': Kwashiorkor, Protein and the Politics of Nutrition Between Britain and Africa". Social History of Medicine. 34 (2): 553–576. doi:10.1093/shm/hkz107. PMC 8162845. PMID 34084092.

- ^ a b Williams CD (1983) [1933]. "Fifty years ago. Archives of Diseases in Childhood 1933. A nutritional disease of childhood associated with a maize diet". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 58 (7): 550–60. doi:10.1136/adc.58.7.550. PMC 1628206. PMID 6347092.

- ^ Williams CD, Oxon BM, Lond H (1935). "Kwashiorkor: a nutritional disease of children associated with a maize diet. 1935". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81 (12): 912–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)94666-X. PMC 2572388. PMID 14997245. Reprint: Williams CD, Oxon BM, Lond H (2003). "Kwashiorkor: a nutritional disease of children associated with a maize diet. 1935". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81 (12): 912–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)94666-X. PMC 2572388. PMID 14997245.

- ^ Stanton, J. (2001). "Listening to the Ga: Cicely Williams' Discovery of Kwashiorkor on the Gold Coast" (PDF). Women and Modern Medicine. Clio Medica. Vol. 61. pp. 149–171. doi:10.1163/9789004333390_008. ISBN 978-90-04-33339-0. PMID 11603151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.