| Lactose intolerance | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lactase deficiency, hypolactasia, alactasia |

| |

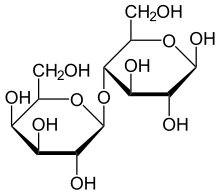

| Lactose is made up of two simple sugars | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, flatulence, nausea[1] |

| Complications | Does not cause damage to the GI tract[2] |

| Usual onset | 30–120 minutes after consuming dairy products[1] |

| Causes | Non-increased ability to digest lactose (genetic, small intestine injury)[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, milk allergy[1] |

| Treatment | Decreasing lactose in the diet, lactase supplements, treat the underlying cause[1] |

| Medication | Lactase |

| Frequency | ~65% of people worldwide (less common in Europeans and East Africans)[3] |

Lactose intolerance is caused by a lessened ability or a complete inability to digest lactose, a sugar found in dairy products.[1] Humans vary in the amount of lactose they can tolerate before symptoms develop.[1] Symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, flatulence, and nausea.[1] These symptoms typically start thirty minutes to two hours after eating or drinking something containing lactose,[1] with the severity typically depending on the amount consumed.[1] Lactose intolerance does not cause damage to the gastrointestinal tract.[2]

Lactose intolerance is due to the lack of the enzyme lactase in the small intestines to break lactose down into glucose and galactose.[3] There are four types: primary, secondary, developmental, and congenital.[1] Primary lactose intolerance occurs as the amount of lactase declines as people grow up.[1] Secondary lactose intolerance is due to injury to the small intestine. Such injury could be the result of infection, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or other diseases.[1][4] Developmental lactose intolerance may occur in premature babies and usually improves over a short period of time.[1] Congenital lactose intolerance is an extremely rare genetic disorder in which little or no lactase is made from birth.[1] The reduction of lactase production starts typically in late childhood or early adulthood,[1] but prevalence increases with age.[5]

Diagnosis may be confirmed if symptoms resolve following eliminating lactose from the diet.[1] Other supporting tests include a hydrogen breath test and a stool acidity test.[1] Other conditions that may produce similar symptoms include irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.[1] Lactose intolerance is different from a milk allergy.[1] Management is typically by decreasing the amount of lactose in the diet, taking lactase supplements, or treating the underlying disease.[1][6] People are typically able to drink at least one cup of milk without developing symptoms, with greater amounts tolerated if drunk with a meal or throughout the day.[1][7]

Worldwide, around 65% of adults are affected by lactose malabsorption.[5][8] Other mammals usually lose the ability to digest lactose after weaning. Lactose intolerance is the ancestral state of all humans before the recent evolution of lactase persistence in some cultures, which extends lactose tolerance into adulthood.[9] Lactase persistence evolved in several populations independently, probably as an adaptation to the domestication of dairy animals around 10,000 years ago.[10][11] Today the prevalence of lactose tolerance varies widely between regions and ethnic groups.[5] The ability to digest lactose is most common in people of European descent, and to a lesser extent in some parts of the Middle East and Africa.[5][8] Lactose intolerance is most common among people of East Asian descent, with 90% lactose intolerance, and Jewish descent, as well as in many African countries and Arab countries. Traditional food cultures reflect local variations in tolerance[5] and historically many societies have adapted to low levels of tolerance by making dairy products that contain less lactose than fresh milk.[12] The medicalization of lactose intolerance as a disorder has been attributed to biases in research history, since most early studies were conducted amongst populations which are normally tolerant,[9] as well as the cultural and economic importance and impact of milk in countries such as the United States.[13]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Lactose Intolerance". NIDDK. June 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ a b Heyman MB (September 2006). "Lactose intolerance in infants, children, and adolescents". Pediatrics. 118 (3): 1279–86. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1721. PMID 16951027. S2CID 2996092.

- ^ a b Malik TF, Panuganti KK (January 2020). "Lactose Intolerance". (StatPearls [Internet]). StatPearls. PMID 30335318. NBK532285.

- ^ Berni Canani R, Pezzella V, Amoroso A, Cozzolino T, Di Scala C, Passariello A (March 2016). "Diagnosing and Treating Intolerance to Carbohydrates in Children". Nutrients. 8 (3): 157. doi:10.3390/nu8030157. PMC 4808885. PMID 26978392.

- ^ a b c d e Storhaug CL, Fosse SK, Fadnes LT (October 2017). "Country, regional, and global estimates for lactose malabsorption in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2 (10): 738–746. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30154-1. PMID 28690131.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Vandenplas2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, Fernandez JR, Gilsanz V, Gould JB, et al. (February 2010). "NIH consensus development conference statement: Lactose intolerance and health". NIH Consensus and State-Of-The-Science Statements (Consensus Development Conference, NIH. Review). 27 (2): 1–27. PMID 20186234. Archived from the original on 2016-12-18.

- ^ a b Bayless TM, Brown E, Paige DM (May 2017). "Lactase Non-persistence and Lactose Intolerance". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 19 (5): 23. doi:10.1007/s11894-017-0558-9. PMID 28421381. S2CID 2941077.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Genetics of lactase persistence andwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ségurel L, Bon C (August 2017). "On the Evolution of Lactase Persistence in Humans". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 18 (1): 297–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035340. PMID 28426286.

- ^ Ingram CJ, Mulcare CA, Itan Y, Thomas MG, Swallow DM (January 2009). "Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence". Human Genetics. 124 (6): 579–91. doi:10.1007/s00439-008-0593-6. PMID 19034520. S2CID 3329285.

- ^ Silanikove N, Leitner G, Merin U (31 August 2015). "The Interrelationships between Lactose Intolerance and the Modern Dairy Industry: Global Perspectives in Evolutional and Historical Backgrounds". Nutrients. 7 (9): 7312–7331. doi:10.3390/nu7095340. PMC 4586535. PMID 26404364.

- ^ Wiley AS (2004). ""Drink Milk for Fitness": The Cultural Politics of Human Biological Variation and Milk Consumption in the United States". American Anthropologist. 106 (3): 506–517. doi:10.1525/aa.2004.106.3.506. JSTOR 3567615.