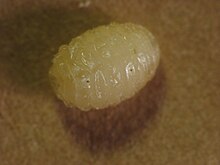

A larva (/ˈlɑːrvə/; pl.: larvae /ˈlɑːrviː/) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

A larva's appearance is generally very different from the adult form (e.g. caterpillars and butterflies) including different unique structures and organs that do not occur in the adult form. Their diet may also be considerably different. In the case of smaller primitive arachnids, the larval stage differs by having three instead of four pairs of legs.[1]

Larvae are frequently adapted to different environments than adults. For example, some larvae such as tadpoles live almost exclusively in aquatic environments, but can live outside water as adult frogs. By living in a distinct environment, larvae may be given shelter from predators and reduce competition for resources with the adult population.

Animals in the larval stage will consume food to fuel their transition into the adult form. In some organisms like polychaetes and barnacles, adults are immobile but their larvae are mobile, and use their mobile larval form to distribute themselves.[2][3] These larvae used for dispersal are either planktotrophic (feeding) or lecithotrophic (non-feeding).

Some larvae are dependent on adults to feed them. In many eusocial Hymenoptera species, the larvae are fed by female workers. In Ropalidia marginata (a paper wasp) the males are also capable of feeding larvae but they are much less efficient, spending more time and getting less food to the larvae.[4]

The larvae of some organisms (for example, some newts) can become pubescent and do not develop further into the adult form. This is a type of neoteny.[5]

It is a misunderstanding that the larval form always reflects the group's evolutionary history. This could be the case, but often the larval stage has evolved secondarily, as in insects.[6][7] In these cases[clarification needed], the larval form may differ more than the adult form from the group's common origins.[8]

- ^ "TICK IDENTIFICATION". Division of environmental health. 4 October 2024.

- ^ Qian, Pei-Yuan (1999), "Larval settlement of polychaetes", Reproductive Strategies and Developmental Patterns in Annelids, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 239–253, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2887-4_14, ISBN 978-90-481-5340-4

- ^ Chen, Zhang-Fan; Zhang, Huoming; Wang, Hao; Matsumura, Kiyotaka; Wong, Yue Him; Ravasi, Timothy; Qian, Pei-Yuan (2014-02-13). "Quantitative Proteomics Study of Larval Settlement in the Barnacle Balanus amphitrite". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88744. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988744C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088744. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3923807. PMID 24551147.

- ^ Sen, R; Gadagkar, R (2006). "Males of the social wasp Ropalidia marginata can feed larvae, given an opportunity". Animal Behaviour. 71 (2): 345–350. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.04.022. S2CID 39848913.

- ^ Wakahara, Masami (1996). "Heterochrony and Neotenic Salamanders: Possible Clues for Understanding the Animal Development and Evolution". Zoological Science. 13 (6): 765–776. doi:10.2108/zsj.13.765 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0289-0003. PMID 9107136. S2CID 35101681.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Nagy, Lisa M.; Grbić, Miodrag (1999), "Cell Lineages in Larval Development and Evolutions of Holometabolous Insects", The Origin and Evolution of Larval Forms, Elsevier, pp. 275–300, doi:10.1016/b978-012730935-4/50010-9, ISBN 978-0-12-730935-4

- ^ Raff, Rudolf A (2008-01-11). "Origins of the other metazoan body plans: the evolution of larval forms". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1496): 1473–1479. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2237. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2614227. PMID 18192188.

- ^ Williamson, Donald I. (2006). "Hybridization in the evolution of animal form and life-cycle". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 148 (4): 585–602. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00236.x.