In microeconomics, the law of demand is a fundamental principle which states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. In other words, "conditional on all else being equal, as the price of a good increases (↑), quantity demanded will decrease (↓); conversely, as the price of a good decreases (↓), quantity demanded will increase (↑)".[1] Alfred Marshall worded this as: "When we say that a person's demand for anything increases, we mean that he will buy more of it than he would before at the same price, and that he will buy as much of it as before at a higher price".[2] The law of demand, however, only makes a qualitative statement in the sense that it describes the direction of change in the amount of quantity demanded but not the magnitude of change.

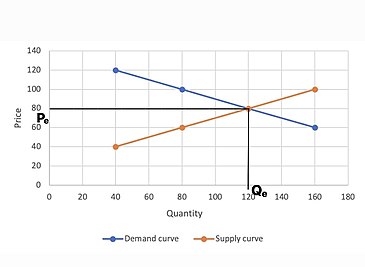

The law of demand is represented by a graph called the demand curve, with quantity demanded on the x-axis and price on the y-axis. Demand curves are downward sloping by definition of the law of demand. The law of demand also works together with the law of supply to determine the efficient allocation of resources in an economy through the equilibrium price and quantity.

The relationship between price and quantity demanded holds true so long as it is complied with the ceteris paribus condition "all else remain equal" quantity demanded varies inversely with price when income and the prices of other goods remain constant.[3] If all else are not held equal, the law of demand may not necessarily hold.[4] In the real world, there are many determinants of demand other than price, such as the prices of other goods, the consumer's income, preferences etc.[5] There are also exceptions to the law of demand such as Giffen goods and perfectly inelastic goods.

- ^ Nicholson, Walter; Snyder, Christopher (2012). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions (11 ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western. pp. 27, 154. ISBN 978-111-1-52553-8.

- ^ Marshall Abhishek, Alfred (1892). Elements of economics of industry. London: Macmillan. pp. 77, 79.

- ^ "Law of Demand: What it is, Definition, Examples". Mundanopedia. 2021-12-31. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ^ "The Law of Demand | Introduction to Business [Deprecated]". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ http://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/lawofdemand.asp; Investopedia, Retrieved 9 September 2013