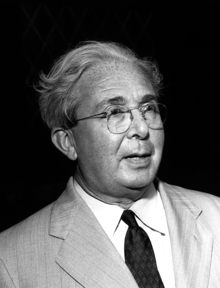

Leo Szilard | |

|---|---|

Szilard, c. 1960 | |

| Born | Leó Spitz February 11, 1898 |

| Died | May 30, 1964 (aged 66) San Diego, California, US |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, biology |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (1923) |

| Doctoral advisor | Max von Laue |

| Other academic advisors | Albert Einstein |

| Signature | |

Leo Szilard (/ˈsɪlɑːrd/; Hungarian: Szilárd Leó [ˈsilaːrd ˈlɛoː]; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-born physicist, biologist and inventor who made numerous important discoveries in nuclear physics and the biological sciences. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, and patented the idea in 1936. In late 1939 he wrote the letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb, and then in 1944 wrote the Szilard petition asking President Truman to demonstrate the bomb without dropping it on civilians. According to György Marx, he was one of the Hungarian scientists known as The Martians.[1]

Szilard initially attended Palatine Joseph Technical University in Budapest, but his engineering studies were interrupted by service in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. He left Hungary for Germany in 1919, enrolling at Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg (now Technische Universität Berlin), but became bored with engineering and transferred to Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he studied physics. He wrote his doctoral thesis on Maxwell's demon, a long-standing puzzle in the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics. Szilard was the first scientist of note to recognize the connection between thermodynamics and information theory.

Szilard coined and submitted the earliest known patent applications and the first publications for the concept of the electron microscope (1928), the cyclotron (1929), and also contributed to the development of the linear accelerator (1928) in Germany. Between 1926 and 1930, he worked with Einstein on the development of the Einstein refrigerator.

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Szilard urged his family and friends to flee Europe while they still could. He moved to England, where he helped found the Academic Assistance Council, an organization dedicated to helping refugee scholars find new jobs. While in England, Szilard, alongside Thomas A. Chalmers, discovered a means of isotope separation known as the Szilard–Chalmers effect.

Foreseeing another war in Europe, Szilard moved to the United States in 1938, where he worked with Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn on means of creating a nuclear chain reaction. He was present when this was achieved within the Chicago Pile-1 on December 2, 1942. He worked for the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago on aspects of nuclear reactor design, where he was the chief physicist. He drafted the Szilard petition advocating a non-lethal demonstration of the atomic bomb, but the Interim Committee chose to use them in a military strike instead.

Together with Enrico Fermi, he applied for a nuclear reactor patent in 1944. He publicly sounded the alarm against the possible development of salted thermonuclear bombs, a new kind of nuclear weapon that might annihilate mankind.

His inventions, discoveries, and contributions related to biological science are also equally important, they include the discovery of feedback inhibition and the invention of the chemostat. According to Theodore Puck and Philip I. Marcus, Szilard gave essential advice which made the earliest cloning of the human cell a reality.

Diagnosed with bladder cancer in 1960, he underwent a cobalt-60 treatment that he had designed. He helped found the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, where he became a resident fellow. Szilard founded Council for a Livable World in 1962 to deliver "the sweet voice of reason" about nuclear weapons to Congress, the White House, and the American public. He died in his sleep of a heart attack in 1964.

- ^ Marx, György. "A marslakók legendája". Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2020.