Levellers | |

|---|---|

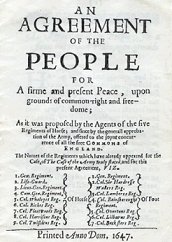

An Agreement of the People, a series of manifestos, published between 1647 and 1649, for constitutional changes to the English state often associated with the Levellers | |

| Leaders | John Lilburne Richard Overton William Walwyn Thomas Prince |

| Founded | July 1646 |

| Dissolved | September 1649 |

| Split from | Roundheads |

| Succeeded by | Radical Whigs |

| Ideology | Radicalism Republicanism Universal suffrage Populism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| National affiliation | Roundheads |

| Military wing | Agitators |

| Colours | Sea green |

The Levellers were a political movement active during the English Civil War who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populism, as shown by its emphasis on equal natural rights, and their practice of reaching the public through pamphlets, petitions and vocal appeals to the crowd.[1]

The Levellers came to prominence at the end of the First English Civil War (1642–1646) and were most influential before the start of the Second Civil War (1648–49). Leveller views and support were found in the populace of the City of London and in some regiments in the New Model Army. Their ideas were presented in their manifesto "Agreement of the People". In contrast to the Diggers, the Levellers opposed common ownership, except in cases of mutual agreement of the property owners.

They were organised at the national level, with offices in a number of London inns and taverns such as The Rosemary Branch in Islington, which got its name from the sprigs of rosemary that Levellers wore in their hats as a sign of identification. They also identified themselves by sea-green ribbons worn on their clothing.

From July 1648 to September 1649, they published a newspaper, The Moderate,[2] and were pioneers in the use of petitions and pamphleteering to political ends.[3][4] London's printing and bookselling trade was pivotal to the movement. [5]

After Pride's Purge and the execution of Charles I, power lay in the hands of the Grandees in the Army (and to a lesser extent with the Rump Parliament). The Levellers, along with all other opposition groups, were marginalised by those in power and their influence waned. By 1650, they were no longer a serious threat to the established order.

- ^ Foxley, Rachel (2013). The Levellers: Radical Political Thought in the English Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0719089367 – via Google Books.

- ^ Howell; Brewster (September 1970). "Reconsidering the Levellers: The Evidence of the Moderate". Past & Present (46): 68–86.

- ^ "Levelers". Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. 2001–2007. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ Plant, David (14 December 2005). "The Levellers". British Civil Wars and Commonwealth website. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ Baker, Philip (2013). "Londons Liberty in Chains Discovered: The Levellers, the Civic Past, and Popular Protest in Civil War London". Huntington Library Quarterly. 76 (4): 559–587. doi:10.1525/hlq.2013.76.4.559.