The Linotype machine (/ˈlaɪnətaɪp/ LYNE-ə-type) is a "line casting" machine used in printing which is manufactured and sold by the former Mergenthaler Linotype Company and related companies.[1] It was a hot metal typesetting system that cast lines of metal type for one-time use. Linotype became one of the mainstays for typesetting, especially small-size body text, for newspapers, magazines, and posters from the late 19th century to the 1970s and 1980s,[1] when it was largely replaced by phototypesetting and digital typesetting. The name of the machine comes from producing an entire line of metal type at once, hence a line-o'-type. It was a significant improvement over the previous industry standard of letter-by-letter manual typesetting using a composing stick and shallow subdivided trays, called "cases".

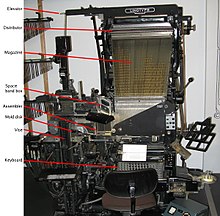

The Linotype machine operator enters text on a 90-character keyboard. The machine assembles matrices, or molds for the letter forms, in a line. The assembled line is then cast as a single piece, called a slug, from molten type metal in a process known as hot metal typesetting. The matrices are then returned to the type magazine, to be reused continuously. This allows much faster typesetting and composition than hand composition in which operators place down one pre-cast sort (metal letter, punctuation mark or space) at a time.

The machine revolutionized typesetting and with it newspaper publishing, making it possible for a relatively small number of operators to set type for many pages daily. Ottmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype in 1884 alongside James Ogilvie Clephane, who provided the financial backing for commercialization.

- ^ a b "End of story for Linotype". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). UPI. November 26, 1970. p. 20B.