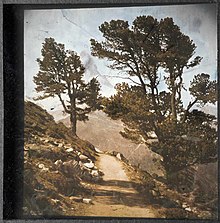

Lippmann process photography is an early color photography method and type of alternative process photography. It was invented by French scientist Gabriel Lippmann in 1891 and consists of first focusing an image onto a light-sensitive plate, placing the emulsion in contact with a mirror (originally liquid mercury) during the exposure to introduce interference, chemically developing the plate, inverting the plate and painting the glass black, and finally affixing a prism to the emulsion surface. The image is then viewed by illuminating the plate with light. This type of photography became known as interferential photography or interferometric colour photography and the results it produces are sometimes called direct photochromes, interference photochromes, or Lippmann photochromes (distinguished from the earlier so-called "photochromes" which were merely black-and-white photographs painted with color by hand).[1][2] In French, the method is known as photographie interférentielle and the resulting images were originally exhibited as des vues lippmaniennes. Lippmann won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1908 "for his method of reproducing colours photographically based on the phenomenon of interference".[3]

Images made with this method are created on a Lippmann plate: a clear glass plate (having no anti-halation backing), coated with an almost transparent (very low silver halide content) emulsion of extremely fine grains, typically 0.01 to 0.04 micrometres in diameter.[4] Consequently, Lippmann plates have an extremely high resolving power[5] exceeding 400 lines/mm.

- ^ Eder, J.M. (1945) [1932]. History of Photography, 4th. edition [Geschichte der Photographie]. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 668, 670, 671, 672. ISBN 0-486-23586-6.

- ^ US 6556992

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1908". NobelPrize.org. Stockholm: Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ R.W.G. Hunt, The Reproduction of Colour, 6th ed, p6

- ^ "Emulsion Definition". www.tpub.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2022.