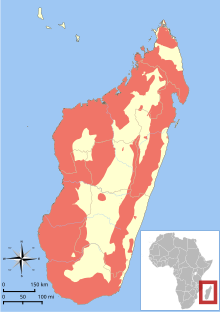

Lemuroidea is a superfamily of primates. Members of this superfamily are called lemuroids, or lemurs. Lemuroidea is one of two superfamilies that form the suborder Strepsirrhini, itself one of two suborders in the order Primates. They are found exclusively on the island of Madagascar, primarily in forests but with some species also in savannas, shrublands, or wetlands. They range in size from the Margot Marsh's mouse lemur, at 8 cm (3 in) plus a 11 cm (4 in) tail, to the indri, at 90 cm (35 in) plus a 6 cm (2 in) tail. Lemuroids primarily eat fruit, leaves, and insects. Most lemuroids do not have population estimates, but the ones that do range from 40 mature individuals to 5,000. Most lemuroid species are at risk of extinction, with 45 species categorized as endangered, and a further 32 species categorized as critically endangered.

The 107 extant species of Lemuroidea are divided into five families. Cheirogaleidae contains 41 dwarf, mouse, and fork-marked lemur species in five genera. Daubentoniidae contains a single species, the aye-aye. Indriidae contains nineteen woolly lemur and sifaka species in three genera. Lemuridae contains 21 ruffed, ring-tailed, bamboo, and other lemur species in five genera. Lepilemuridae contains 25 sportive lemur species in a single genus.

Dozens of extinct prehistoric lemuroid species have been discovered, though due to ongoing research and discoveries the exact number and categorization is not fixed.[1] At least 17 species and eight genera are believed to have become extinct in the 2,000 years since humans first arrived in Madagascar.[2][3] All known extinct species were large, ranging in weight from 10 to 200 kg (22 to 441 lb). The largest known subfossil lemur was Archaeoindris fontoynonti, a giant sloth lemur, which weighed more than a modern female gorilla. The extinction of the largest lemurs is often attributed to predation by humans and possibly habitat destruction.[2] Since all extinct lemurs were not only large (and thus ideal prey species), but also slow-moving (and thus more vulnerable to human predation), their presumably slow-reproducing and low-density populations were least likely to survive the introduction of humans.[2] Gradual changes in climate have also been blamed, and may have played a minor role; however since the largest lemurs also survived the climatic changes from previous ice ages and only disappeared following the arrival of humans, it is unlikely that climatic change was largely responsible.[2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PDBLemuroideawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Mittermeier, pp. 50–51

- ^ Gommery, D.; Ramanivosoa, B.; Tombomiadana-Raveloson, S.; Randrianantenaina, H.; Kerloc'h, P. (2009). "A new species of giant subfossil lemur from the North-West of Madagascar (Palaeopropithecus kelyus, Primates)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 8 (5): 471–480. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2009.02.001.

- "New Extinct Lemur Species Discovered In Madagascar". ScienceDaily (Press release). 27 May 2009.