This is a list of slave traders of the United States, people whose occupation or business was the slave trade in the United States, i.e. the buying and selling of human chattel as commodities, primarily African-American people in the Southern United States, from the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776 until the defeat of the Confederate States of America in 1865.

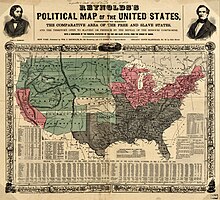

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves was passed in 1808 under the so-called Star-Spangled Banner flag, when there were 15 states in the Union, closing the transatlantic slave trade and setting the stage for the interstate slave trade in the U.S. Over 50 years later, in 1865, the last American slave sale was made somewhere in the rebel Confederacy.[3] In the intervening years, the politics surrounding the addition of 20 new states to the Union had been almost overwhelmingly dominated by whether or not those states would have legal slavery.[4]

Slavery was widespread, so slave trading was widespread, and "When a planter died, failed in business, divided his estate, needed ready money to satisfy a mortgage or pay a gambling debt, or desired to get rid of an unruly Negro, traders struck a profitable bargain."[5] A slave trader might have described himself as a broker, auctioneer, general agent, or commission merchant,[6] and often sold real estate, personal property, and livestock in addition to enslaved people.[7] Many large trading firms also had field agents, whose job it was to go to more remote towns and rural areas, buying up enslaved people for resale elsewhere.[3] Field agents stood lower in the hierarchy, and are generally poorly studied, in part due to lack of records, but field agents for Austin Woolfolk, for example, "served only a year or two at best and usually on a part-time basis. No fortunes were to be made as local agents."[8] On the other end of the financial spectrum from the agents were the investors—usually wealthy planters like David Burford,[9] John Springs III,[10] and Chief Justice John Marshall[11]—who fronted cash to slave speculators. They did not escort coffles or run auctions themselves, but they did parlay their enslaving expertise into profits. Also, especially in the first quarter of the 19th century, cotton factors, banks, and shipping companies did a great deal of slave trading business as part of what might be called the "vertical integration" of cotton and sugar industries.

Countless slaves were also sold at courthouse auctions by county sheriffs and U.S. marshals to satisfy court judgments, settle estates, and to "cover jail fees"; individuals involved in those sales are not the primary focus of this list. People who dealt in enslaved indigenous persons, such as was the case with slavery in California, would be included. Slave smuggling took advantage of international and tribal boundaries to traffic slaves into the United States from Spanish North American and Caribbean colonies, and across the lands of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee, Seminole, et al., but American-born or naturalized smugglers, Indigenous slave traders, and any American buyers of smuggled slaves would be included.

Note: Research by Michael Tadman has found that "'core' sources provide only a basic skeleton of a much more substantial trade" in enslaved people throughout the South, with particular deficits in records of rural slave trading, already wealthy people who speculated to grow their wealth further, and in all private sales that occurred outside auction houses and negro marts.[10] This list represents a fraction of the "many hundreds of participants in a cruel and omnipresent" American market.[12]

List is organized by surname of trader, or name of firm, where principals have not been further identified.

Note: Charleston and Charles Town, Virginia are distinct places that later became Charleston, West Virginia, and Charles Town, West Virginia, respectively, and neither is to be confused with Charleston, South Carolina.

We must have a market for human flesh, or we are ruined.

— Frederick Douglass, on the predominant message from the Southern states to the U.S. government before the American Civil War, The Frederick Douglass Papers, vol. II, p. 405

- ^ CAMP (1865). The Camp of Freedom. A Plea for the Coloured Freedman. Reprinted from the "Eclectic" for April, 1865. George Watson. p. 7.

- ^ Blassingame, John W. (1973). "Before the Ghetto: The Making of the Black Community in Savannah, Georgia, 1865-1880". Journal of Social History. 6 (4): 463–488. doi:10.1353/jsh/6.4.463. ISSN 0022-4529. JSTOR 3786511.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Dew2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rothman, A. (April 1, 2009). "Slavery and National Expansion in the United States". OAH Magazine of History. 23 (2): 23–29. doi:10.1093/maghis/23.2.23. ISSN 0882-228X.

- ^ Sherwin, Oscar (1945). "Trading in Negroes". Negro History Bulletin. 8 (7): 160–166. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44214396.

- ^ Bancroft (2023), p. 96.

- ^ Bancroft (2023), p. 125.

- ^ Calderhead (1977), p. 197.

- ^ Purcell, Aaron D. (2005). "A Spirit for speculation: David Burford, Antebellum Entrepreneur of Middle Tennessee". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 64 (2): 90–109. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42631252.

- ^ a b Tadman, Michael (1996). "The Hidden History of Slave Trading in Antebellum South Carolina: John Springs III and Other "Gentlemen Dealing in Slaves"". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 97 (1): 6–29. ISSN 0038-3082. JSTOR 27570133.

- ^ Westmoreland, Carl B. (2015). "Article 3: The John W. Anderson Slave Pen". Freedom Center Journal. 2015 (1). University of Cincinnati College of Law. ISSN 1942-5856.

- ^ Tadman, Michael (September 18, 2012). "Chapter 28. Internal Slave Trades". In Smith, Mark M.; Paquette, Robert L. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199227990.013.0029.

- ^ Johnson (2009), p. 48.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Letters of a Traveller, by William Cullen Bryant". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ "The Ottawa Free Trader 08 Nov 1856, page Page 1". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-08-15.