This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2022) |

| Long-eared owl | |

|---|---|

| |

| A long-eared owl in Hungary | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Asio |

| Species: | A. otus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Asio otus | |

| |

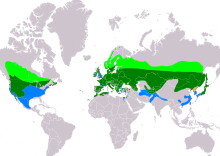

| Range of A. otus Breeding Resident Non-breeding Extant (seasonality uncertain)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The long-eared owl (Asio otus), also known as the northern long-eared owl[3] or, more informally, as the lesser horned owl or cat owl,[4] is a medium-sized species of owl with an extensive breeding range. The genus name, Asio, is Latin for "horned owl", and the specific epithet, otus, is derived from Greek and refers to a small eared owl.[5] The species breeds in many areas through Europe and the Palearctic, as well as in North America. This species is a part of the larger grouping of owls known as typical owls, of the family Strigidae, which contains most extant species of owl.[6][7][8]

This owl shows a partiality for semi-open habitats, particularly woodland edge, as they prefer to roost and nest within dense stands of wood but prefer to hunt over open ground.[8][9] The long-eared owl is a somewhat specialized predator, focusing its diet almost entirely on small rodents, especially voles, which quite often compose most of their diet.[4][8] Under some circumstances, such as population cycles of their regular prey, arid or insular regional habitats or urbanization, this species can adapt fairly well to a diversity of prey, including birds and insects.[4][10][11][12] All owls do not build their own nests. In the case of the long-eared owl, it generally utilizes nests that are built by other animals, with a partiality in many regions for those built by corvids.[13][14] Breeding success in this species is largely correlated with prey populations and predation risks.[4][13][14] Unlike many owls, long-eared owls are not strongly territorial or sedentary. They are partially migratory and, although owls appear to generally use the same migratory routes and wintering sites annually, can tend to appear so erratically that they are sometimes characterized as “nomadic”.[15] Another fairly unique characteristic of this species is its partiality for regular roosts that are often shared by a number of long-eared owls at once.[16][17] The long-eared owl is one of the most widely distributed and most numerous owl species in the world, and due to its very broad range and numbers it is considered a least concern species by the IUCN. Nonetheless, strong declines have been detected for this owl in several parts of its range.[1][18]

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Asio otus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22689507A131922722. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22689507A131922722.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Olsen, P.D. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Northern Long-eared Owl (Asio otus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ^ a b c d Voous, K.H. (1988). Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. The MIT Press, ISBN 0262220350.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 57, 286. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Weick, Friedhelm (2007). Owls (Strigiformes): Annotated and Illustrated Checklist. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-39567-6.

- ^ Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide by Mikkola, H. Firefly Books (2012), ISBN 9781770851368

- ^ a b c König, Claus; Weick, Friedhelm (2008). Owls of the World (2nd ed.). London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 9781408108840.

- ^ Johnsgard, P. A. (1988). North American owls: biology and natural history. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Kiat, Y., Perlman, G., Balaban, A., Leshem, Y., Izhaki, I., & Charter, M. (2008). Feeding specialization of urban Long-eared Owls, Asio otus (Linnaeus, 1758), in Jerusalem, Israel. Zoology in the Middle East, 43(1), 49-54.

- ^ Trujillo, O., Díaz, G., & Moreno, M. (1989). Alimentación del búho chico (Asio otus canariensis) en Gran Canaria (Islas Canarias). Ardeola, 36(2), 193-231.

- ^ Village, A. (1981). The diet and breeding of Long-eared Owls in relation to vole numbers. Bird Study, 28(3), 214-224.

- ^ a b Marks, J. S. (1986). Nest-site characteristics and reproductive success of Long-eared Owls in southwestern Idaho. The Wilson Bulletin, 547-560.

- ^ a b Glue, D. E. (1977). Breeding biology of Long-eared Owls. British Birds, 70(8), 318-331.

- ^ Houston, C. S. (1997). Banding of Asio owls in south-central Saskatchewan. In In: Duncan, James R.; Johnson, David H.; Nicholls, Thomas H., eds. Biology and conservation of owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International symposium. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190. St. Paul, MN: US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station. 237-242. (Vol. 190).

- ^ Pirovano, A., Rubolini, D., & de Michelis, S. (2000). Winter roost occupancy and behaviour at evening departure of urban long‐eared owls. Italian Journal of Zoology, 67(1), 63-66.

- ^ Bosakowski, T. (1984). Roost selection and behavior of the Long-eared Owl (Asio otus) wintering in New Jersey. Raptor Res, 18(13), 7-142.

- ^ Kirk, D. A., & Hyslop, C. (1998). Population status and recent trends in Canadian raptors: a review. Biological Conservation, 83(1), 91-118.