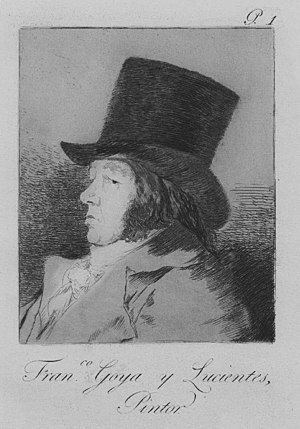

Los Caprichos (The Caprices) is a set of 80 prints in aquatint and etching created by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya in 1797–1798 and published as an album in 1799. The prints were an artistic experiment: a medium for Goya's satirizing Spanish society at the end of the 18th century, particularly the nobility and the clergy. Goya in his plates humorously and mercilessly criticized society while aspiring to more just laws and a new educational system. Closely associated with the Enlightenment, the criticisms are far-ranging and acidic. The images expose the predominance of superstition, religious fanaticism, the Inquisition, religious orders, the ignorance and inabilities of the various members of the ruling class, pedagogical shortcomings, marital mistakes, and the decline of rationality.[1]

Goya added brief explanations of each image to a manuscript, now in the Museo del Prado, which help explain his often cryptic intentions, as do the titles printed below each image. Aware of the risk he was taking, to protect himself, he gave many of his prints imprecise labels, especially the satires of the aristocracy and the clergy. He also diluted the messaging by illogically arranging the engravings. Goya explained in an announcement that he chose subjects "from the multitude of faults and vices common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudices and lies authorized by custom, ignorance or self-interest, those that he has thought most suitable matter for ridicule".

Despite the relatively vague language of Goya's captions in the Caprichos, Goya’s contemporaries understood the engravings, even the most ambiguous ones, as a direct satire of their society, even alluding to specific individuals, though the artist always denied the associations.

The series was published in February 1799; however, just 14 days after going on sale, when Manuel Godoy and his affiliates lost power, the painter hastily withdrew the copies still available for fear of the Inquisition. In 1807, to save the Caprichos, Goya decided to offer the king the plates and the 240 unsold copies, destined for the Royal Calcography, in exchange for a lifetime pension of twelve thousand reales per year for his son Javier.[2]

The work was a tour-de-force critique of 18th-century Spain, and humanity in general, from the point of view of the Enlightenment. The informal style, as well as the depiction of contemporary society found in Caprichos, makes them (and Goya himself) a precursor to the modernist movement almost a century later. Capricho No. 43, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in particular has attained an iconic status.

Goya's series, and the last group of prints in his series The Disasters of War, which he called "caprichos enfáticos" ("emphatic caprices"), are far from the spirit of light-hearted fantasy the term "caprice" usually suggests in art.

Thirteen official editions are known: one from 1799, five in the 19th century, and seven in the 20th century, with the last one in 1970 being carried out by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando.

Los Caprichos have influenced generations of artists from movements as diverse as French Romanticism, Impressionism, German Expressionism or Surrealism. Ewan MacColl and André Malraux considered Goya one of the precursors of modern art, citing the innovations and ruptures of the Caprichos.

- ^ Simon, Linda, "The Sleep of Reason", The World and I

- ^ Gudiol, José (1984). Goya. Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, S.A. p. 20. ISBN 9788434304048.