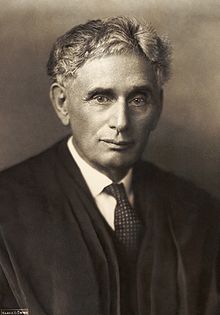

Louis Brandeis | |

|---|---|

Brandeis c. 1916 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office June 5, 1916 – February 13, 1939[1] | |

| Nominated by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Joseph Lamar |

| Succeeded by | William O. Douglas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Louis David Brandeis November 13, 1856 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 5, 1941 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (before 1912) Democratic (after 1912)[2] |

| Spouse |

Alice Goldmark (m. 1891) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Harvard University (LLB) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United States |

|---|

|

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (/ˈbrændaɪs/; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the "right to privacy" concept by writing a Harvard Law Review article of that title,[3] and was thereby credited by legal scholar Roscoe Pound as having accomplished "nothing less than adding a chapter to our law." He was a leading figure in the antitrust movement at the turn of the century, particularly in his resistance to the monopolization of the New England railroad and advice to Woodrow Wilson as a candidate. In his books, articles and speeches, including Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It, and The Curse of Bigness, he criticized the power of large banks, money trusts, powerful corporations, monopolies, public corruption, and mass consumerism, all of which he felt were detrimental to American values and culture. He later became active in the Zionist movement, seeing it as a solution to antisemitism in Europe and Russia, while at the same time being a way to "revive sense of the Jewish spirit."

When his family's finances became secure, he began devoting most of his time to public causes, and he was later dubbed the "People's Lawyer."[4] He insisted on taking cases without pay so that he would be free to address the wider issues involved. The Economist magazine called him "A Robin Hood of the law."[5] Among his notable early cases were actions fighting railroad monopolies, defending workplace and labor laws, helping create the Federal Reserve System, and presenting ideas for the new Federal Trade Commission. He achieved recognition by submitting a case brief, later called the "Brandeis brief", which relied on expert testimony from people in other professions to support his case, thereby setting a new precedent in evidence presentation.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson nominated Brandeis to a seat on the Supreme Court of the United States. His nomination was bitterly contested, partly because, as Justice William O. Douglas later wrote, "Brandeis was a militant crusader for social justice whoever his opponent might be. He was dangerous not only because of his brilliance, his arithmetic, his courage. He was dangerous because he was incorruptible ... [and] the fears of the Establishment were greater because Brandeis was the first Jew to be named to the Court."[6] On June 1, 1916, he was confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 47 to 22,[6] to become one of the most famous and influential figures ever to serve on the high court. His opinions were, according to legal scholars, some of the "greatest defenses" of freedom of speech and the right to privacy ever written by a member of the Supreme Court. Some have criticized Brandeis for evading issues related to African-Americans, as he did not author a single opinion on any cases about race during his twenty-three year tenure, and he consistently voted with the Supreme Court majority including in support of racial segregation.

- ^ "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Marc Eric McClure (2003). Earnest Endeavors: The Life and Public Work of George Rublee. Greenwood. p. 76. ISBN 9780313324093. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 Harv. L. Rev. 193 (1890), available at HeinOnline Archived October 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "About". brandeis.edu. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "Let's look at the facts". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Douglas, William O. (July 5, 1964). "Louis Brandeis: Dangerous Because Incorruptible". The New York Times. p. BR3. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2020.