| Malignant hyperthermia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Malignant hyperpyrexia, anesthesia related hyperthermia[1] |

| |

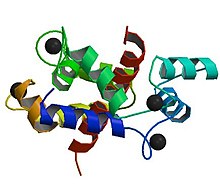

| Abnormalities in the ryanodine receptor 1 gene are commonly detected in people who have experienced an episode of malignant hyperthermia | |

| Specialty | Anesthesiology, critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Muscle rigidity, high body temperature, fast heart rate[1] |

| Complications | Rhabdomyolysis, high blood potassium[1][2] |

| Causes | Volatile anesthetic agents or succinylcholine in those who are susceptible[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and situation[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Sepsis, anaphylaxis, serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome[3] |

| Prevention | Avoiding potential triggers in those susceptible[2] |

| Treatment | Dantrolene, supportive care[4] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death: 5% (treatment), 75% (no treatment)[3] |

| Frequency | ~1 in 25,000 cases where anesthetic gases are used[1] |

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a type of severe reaction that occurs in response to particular medications used during general anesthesia, among those who are susceptible.[1] Symptoms include muscle rigidity, fever, and a fast heart rate.[1] Complications can include muscle breakdown and high blood potassium.[1][2] Most people who are susceptible to MH are generally unaffected when not exposed to triggering agents.[3]

Exposure to triggering agents (certain volatile anesthetic agents or succinylcholine) can lead to the development of MH in those who are susceptible.[1][3] Susceptibility can occur due to at least six genetic mutations, with the most common one being of the RYR1 gene.[1] These genetic variations are often inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.[1] The condition may also occur as a new mutation or be associated with a number of inherited muscle diseases, such as central core disease.[1][4]

In susceptible individuals, the medications induce the release of stored calcium ions within muscle cells.[1] The resulting increase in calcium concentrations within the cells cause the muscle fibers to contract.[1] This generates excessive heat and results in metabolic acidosis.[1] Diagnosis is based on symptoms in the appropriate situation.[2] Family members may be tested to see if they are susceptible by muscle biopsy or genetic testing.[4]

Treatment is with dantrolene and rapid cooling along with other supportive measures.[2][4] The avoidance of potential triggers is recommended in susceptible people.[2] The condition affects one in 5,000 to 50,000 cases where people are given anesthetic gases.[1] Males are more often affected than females.[3] The risk of death with proper treatment is about 5% while without it is around 75%.[3] While cases that appear similar to MH have been documented since the early 20th century, the condition was only formally recognized in 1960.[3]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "malignant hyperthermia". Genetics Home Reference. Jan 27, 2017. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Malignant hyperthermia" (PDF). Orpha.net. March 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schneiderbanger, D; Johannsen, S; Roewer, N; Schuster, F (2014). "Management of malignant hyperthermia: diagnosis and treatment". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 10: 355–62. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S47632. PMC 4027921. PMID 24868161.

- ^ a b c d "Malignant hyperthermia". GARD. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.