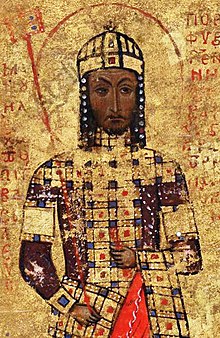

| Manuel I Komnenos | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

Manuscript miniature, part of double portrait with Empress Maria, Vatican Library | |||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 8 April 1143 – 24 September 1180 | ||||

| Predecessor | John II Komnenos | ||||

| Successor | Alexios II Komnenos | ||||

| Born | 28 November 1118 | ||||

| Died | 24 September 1180 (aged 61) | ||||

| Spouses | Bertha of Sulzbach Maria of Antioch | ||||

| Issue | Maria Komnene Alexios II Komnenos | ||||

| |||||

| House | Komnenian dynasty | ||||

| Father | John II Komnenos | ||||

| Mother | Irene of Hungary | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Christian | ||||

Manuel I Komnenos (Greek: Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, romanized: Manouḗl Komnēnós; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized as Comnenus, also called Porphyrogenitus (Greek: Πορφυρογέννητος; "born in the purple"), was a Byzantine emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean. His reign saw the last flowering of the Komnenian restoration, during which the Byzantine Empire experienced a resurgence of military and economic power and enjoyed a cultural revival.

Eager to restore his empire to its past glories as the great power of the Mediterranean world, Manuel pursued an energetic and ambitious foreign policy. In the process he made alliances with Pope Adrian IV and the resurgent West. He invaded the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, although unsuccessfully, being the last Eastern Roman emperor to attempt reconquests in the western Mediterranean. The passage of the potentially dangerous Second Crusade through his empire was adroitly managed. Manuel established a Byzantine protectorate over the Crusader states of Outremer. Facing Muslim advances in the Holy Land, he made common cause with the Kingdom of Jerusalem and participated in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt. Manuel reshaped the political maps of the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean, placing the kingdoms of Hungary and Outremer under Byzantine hegemony and campaigning aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the east.

However, towards the end of his reign, Manuel's achievements in the east were compromised by a serious defeat at Myriokephalon, which in large part resulted from his arrogance in attacking a well-defended Seljuk position. Although the Byzantines recovered and Manuel concluded an advantageous peace with Sultan Kilij Arslan II, Myriokephalon proved to be the final, unsuccessful effort by the empire to recover the interior of Anatolia from the Turks.

Called ho Megas (ὁ Μέγας, translated as "the Great") by the Greeks, Manuel is known to have inspired intense loyalty in those who served him. He also appears as the hero of a history written by his secretary, John Kinnamos, in which every virtue is attributed to him. Manuel, who was influenced by his contact with western Crusaders, enjoyed the reputation of "the most blessed emperor of Constantinople" in parts of the Latin world as well.[1] Some historians have been less enthusiastic about him, however, asserting that the great power he wielded was not his own personal achievement, but that of the Komnenos dynasty he represented. Further, it has also been argued that since Byzantine imperial power declined catastrophically after Manuel's death, it is only natural to look for the causes of this decline in his reign.[2]