| Part of a series on | ||

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

| ||

Mathematics and art are related in a variety of ways. Mathematics has itself been described as an art motivated by beauty. Mathematics can be discerned in arts such as music, dance, painting, architecture, sculpture, and textiles. This article focuses, however, on mathematics in the visual arts.

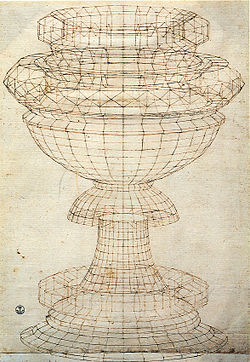

Mathematics and art have a long historical relationship. Artists have used mathematics since the 4th century BC when the Greek sculptor Polykleitos wrote his Canon, prescribing proportions conjectured to have been based on the ratio 1:√2 for the ideal male nude. Persistent popular claims have been made for the use of the golden ratio in ancient art and architecture, without reliable evidence. In the Italian Renaissance, Luca Pacioli wrote the influential treatise De divina proportione (1509), illustrated with woodcuts by Leonardo da Vinci, on the use of the golden ratio in art. Another Italian painter, Piero della Francesca, developed Euclid's ideas on perspective in treatises such as De Prospectiva Pingendi, and in his paintings. The engraver Albrecht Dürer made many references to mathematics in his work Melencolia I. In modern times, the graphic artist M. C. Escher made intensive use of tessellation and hyperbolic geometry, with the help of the mathematician H. S. M. Coxeter, while the De Stijl movement led by Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian explicitly embraced geometrical forms. Mathematics has inspired textile arts such as quilting, knitting, cross-stitch, crochet, embroidery, weaving, Turkish and other carpet-making, as well as kilim. In Islamic art, symmetries are evident in forms as varied as Persian girih and Moroccan zellige tilework, Mughal jali pierced stone screens, and widespread muqarnas vaulting.

Mathematics has directly influenced art with conceptual tools such as linear perspective, the analysis of symmetry, and mathematical objects such as polyhedra and the Möbius strip. Magnus Wenninger creates colourful stellated polyhedra, originally as models for teaching. Mathematical concepts such as recursion and logical paradox can be seen in paintings by René Magritte and in engravings by M. C. Escher. Computer art often makes use of fractals including the Mandelbrot set, and sometimes explores other mathematical objects such as cellular automata. Controversially, the artist David Hockney has argued that artists from the Renaissance onwards made use of the camera lucida to draw precise representations of scenes; the architect Philip Steadman similarly argued that Vermeer used the camera obscura in his distinctively observed paintings.

Other relationships include the algorithmic analysis of artworks by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, the finding that traditional batiks from different regions of Java have distinct fractal dimensions, and stimuli to mathematics research, especially Filippo Brunelleschi's theory of perspective, which eventually led to Girard Desargues's projective geometry. A persistent view, based ultimately on the Pythagorean notion of harmony in music, holds that everything was arranged by Number, that God is the geometer of the world, and that therefore the world's geometry is sacred.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Zieglerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Colombo, C.; Del Bimbo, A.; Pernici, F. (2005). "Metric 3D reconstruction and texture acquisition of surfaces of revolution from a single uncalibrated view". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 27 (1): 99–114. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.58.8477. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2005.14. PMID 15628272. S2CID 13387519.