Maurice Wilkins | |

|---|---|

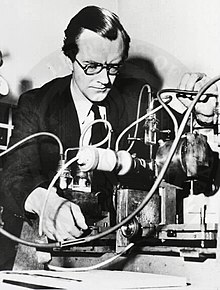

Maurice Wilkins with one of the cameras he developed specially for X-ray diffraction studies at King's College London[1] | |

| Born | Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins 15 December 1916 Pongaroa, New Zealand |

| Died | 5 October 2004 (aged 87) Blackheath, London, England |

| Education | King Edward's School, Birmingham |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge (MA) University of Birmingham (PhD) |

| Known for | X-ray diffraction, DNA |

| Spouses | Ruth Wilkins (divorced)Patricia Ann Chidgey

(m. 1959) |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biophysics Physics |

| Institutions | King's College London University of Birmingham University of California, Berkeley University of St Andrews |

| Thesis | Phosphorescence decay laws and electronic processes in solids (1940) |

| Doctoral advisor | John Randall |

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins CBE FRS (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004)[2] was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding of phosphorescence, isotope separation, optical microscopy, and X-ray diffraction. He is known for his work at King's College London on the structure of DNA.

Wilkins' work on DNA falls into two distinct phases. The first was in 1948–1950, when his initial studies produced the first clear X-ray images of DNA, which he presented at a conference in Naples in 1951 attended by James Watson. During the second phase, 1951–52, Wilkins produced clear "B form" X-shaped images from squid sperm, images he sent to James Watson and Francis Crick, causing Watson to write "Wilkins... has obtained extremely excellent X-ray diffraction photographs" [of DNA].[3][4]

In 1953, Wilkins' group coordinator Sir John Randall instructed Raymond Gosling to hand over to Wilkins a high-quality image of "B" form DNA (Photo 51), which Gosling had made in 1952,[5][6] after which his supervisor Rosalind Franklin "put it aside"[7] as she was leaving King's College London. Wilkins showed it to Watson.[8] This image, along with the knowledge that Linus Pauling had proposed an incorrect structure of DNA, "mobilised"[9] Watson and Crick to restart model building. With additional information from research reports of Wilkins and Franklin, obtained via Max Perutz, Watson and Crick correctly described the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953.

Wilkins continued to test, verify, and make significant corrections to the Watson–Crick DNA model and to study the structure of RNA.[10] Wilkins, Crick, and Watson were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".[11]

- ^ "Science mourns DNA pioneer Wilkins". BBC News. 6 October 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Arnott, S.; Kibble, T. W. B.; Shallice, T. (2006). "Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins. 15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004: Elected FRS 1959". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 52. London: Royal Society: 455–478. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2006.0031. PMID 18551798.

- ^ Robert Olby; The Path to The Double Helix: Discovery of DNA; p366

- ^ James D. Watson, The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix p180

- ^ "Due credit". Nature. 496 (7445): 270. 18 April 2013. doi:10.1038/496270a. PMID 23607133.

- ^ Witkowski J (2019). "The forgotten scientists who paved the way to the double helix". Nature. 568 (7752): 308–309. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..308W. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01176-9.

- ^ Maddox p178

- ^ James D. Watson, The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix p182

- ^ "Linus Pauling and The Race for DNA". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Arnott, Struther. "Crystallography News: An historical memoir in honour of Maurice Wilkins 1916–2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 14 December 2020.