| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intranasal, rectal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–14 hours[2][3] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.026.959 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

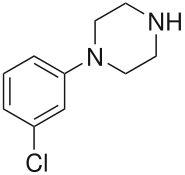

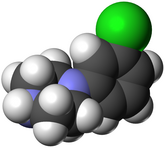

| Formula | C10H13ClN2 |

| Molar mass | 196.68 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

meta-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) is a psychoactive drug of the phenylpiperazine class. It was initially developed in the late-1970s and used in scientific research before being sold as a designer drug in the mid-2000s.[4][5] It has been detected in pills touted as legal alternatives to illicit stimulants in New Zealand and pills sold as "ecstasy" in Europe and the United States.[6][7]

Despite its advertisement as a recreational substance, mCPP is actually generally considered to be an unpleasant experience and is not desired by drug users.[6] It lacks any reinforcing effects, but has "psychostimulant, anxiety-provoking, and hallucinogenic effects."[8][9][10][11] It is also known to produce dysphoric, depressive, and anxiogenic effects in rodents and humans,[12][13] and can induce panic attacks in individuals susceptible to them.[14][15][16][17] It also worsens obsessive–compulsive symptoms in people with the disorder.[18][19][20]

mCPP is known to induce headaches in humans and has been used for testing potential antimigraine medications.[21][22][23] It has potent anorectic effects and has encouraged the development of selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity as well.[24][25][26][27]

- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ a b Rotzinger S, Bourin M, Akimoto Y, Coutts RT, Baker GB (August 1999). "Metabolism of some "second"- and "fourth"-generation antidepressants: iprindole, viloxazine, bupropion, mianserin, maprotiline, trazodone, nefazodone, and venlafaxine". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 19 (4): 427–442. doi:10.1023/a:1006953923305. PMID 10379419. S2CID 19585113.

- ^ Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2017). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 460–. ISBN 978-1-58562-523-9.

- ^ Bossong MG, Van Dijk JP, Niesink RJ (December 2005). "Methylone and mCPP, two new drugs of abuse?". Addiction Biology. 10 (4): 321–323. doi:10.1080/13556210500350794. PMID 16318952. S2CID 36169592. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- ^ Lecompte Y, Evrard I, Arditti J (2006). "[Metachlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP): a new designer drug]". Therapie (in French). 61 (6): 523–530. doi:10.2515/therapie:2006093. PMID 17348609.

- ^ a b Bossong MG, Brunt TM, Van Dijk JP, Rigter SM, Hoek J, Goldschmidt HM, Niesink RJ (September 2010). "mCPP: an undesired addition to the ecstasy market". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (9): 1395–1401. doi:10.1177/0269881109102541. PMID 19304863. S2CID 11186375.

- ^ Vogels N, Brunt TM, Rigter S, van Dijk P, Vervaeke H, Niesink RJ (December 2009). "Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands: 1993-2008". Addiction. 104 (12): 2057–2066. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02707.x. PMID 19804461.

- ^ World Health Organization. "1-(3-chlorophenyl) piperazine (mCPP) - Expert peer review on pre-review report" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Tancer ME, Johanson CE (December 2001). "The subjective effects of MDMA and mCPP in moderate MDMA users". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 65 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00146-6. PMID 11714594.

- ^ Tancer M, Johanson CE (October 2003). "Reinforcing, subjective, and physiological effects of MDMA in humans: a comparison with d-amphetamine and mCPP". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 72 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00172-8. PMID 14563541.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid9933142was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rajkumar R, Pandey DK, Mahesh R, Radha R (April 2009). "1-(m-Chlorophenyl)piperazine induces depressogenic-like behaviour in rodents by stimulating the neuronal 5-HT(2A) receptors: proposal of a modified rodent antidepressant assay". European Journal of Pharmacology. 608 (1–3): 32–41. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.041. PMID 19269287.

- ^ Kennett GA, Whitton P, Shah K, Curzon G (May 1989). "Anxiogenic-like effects of mCPP and TFMPP in animal models are opposed by 5-HT1C receptor antagonists". European Journal of Pharmacology. 164 (3): 445–454. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90252-5. PMID 2767117.

- ^ Klein E, Zohar J, Geraci MF, Murphy DL, Uhde TW (November 1991). "Anxiogenic effects of m-CPP in patients with panic disorder: comparison to caffeine's anxiogenic effects". Biological Psychiatry. 30 (10): 973–984. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90119-7. PMID 1756202. S2CID 43010184.

- ^ Charney DS, Woods SW, Goodman WK, Heninger GR (1987). "Serotonin function in anxiety. II. Effects of the serotonin agonist MCPP in panic disorder patients and healthy subjects". Psychopharmacology. 92 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1007/bf00215473. PMID 3110824. S2CID 43079787.

- ^ Van Veen JF, Van der Wee NJ, Fiselier J, Van Vliet IM, Westenberg HG (October 2007). "Behavioural effects of rapid intravenous administration of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (m-CPP) in patients with generalized social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and healthy controls". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (10): 637–642. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.03.005. PMID 17481859. S2CID 41601926.

- ^ van der Wee NJ, Fiselier J, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG (October 2004). "Behavioural effects of rapid intravenous administration of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in patients with panic disorder and controls". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (5): 413–417. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.01.001. PMID 15336303. S2CID 28987431.

- ^ Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Nitescu A, Gully R, Suckow RF, Cooper TB, et al. (January 1992). "Serotonergic function in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to oral m-chlorophenylpiperazine and fenfluramine in patients and healthy volunteers". Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820010021003. PMID 1728249.

- ^ Broocks A, Pigott TA, Hill JL, Canter S, Grady TA, L'Heureux F, Murphy DL (June 1998). "Acute intravenous administration of ondansetron and m-CPP, alone and in combination, in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): behavioral and biological results". Psychiatry Research. 79 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00029-8. PMID 9676822. S2CID 30339598.

- ^ Pigott TA, Zohar J, Hill JL, Bernstein SE, Grover GN, Zohar-Kadouch RC, Murphy DL (March 1991). "Metergoline blocks the behavioral and neuroendocrine effects of orally administered m-chlorophenylpiperazine in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 29 (5): 418–426. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90264-M. PMID 2018816. S2CID 37648659.

- ^ Leone M, Attanasio A, Croci D, Filippini G, D'Amico D, Grazzi L, et al. (July 2000). "The serotonergic agent m-chlorophenylpiperazine induces migraine attacks: A controlled study". Neurology. 55 (1): 136–139. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.1.136. PMID 10891925. S2CID 27617431.

- ^ Martin RS, Martin GR (February 2001). "Investigations into migraine pathogenesis: time course for effects of m-CPP, BW723C86 or glyceryl trinitrate on appearance of Fos-like immunoreactivity in rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC)". Cephalalgia. 21 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00157.x. PMID 11298663. S2CID 8471836.

- ^ Petkov VD, Belcheva S, Konstantinova E (December 1995). "Anxiolytic effects of dotarizine, a possible antimigraine drug". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 17 (10): 659–668. PMID 9053586.

- ^ Kennett GA, Curzon G (1988). "Evidence that hypophagia induced by mCPP and TFMPP requires 5-HT1C and 5-HT1B receptors; hypophagia induced by RU 24969 only requires 5-HT1B receptors". Psychopharmacology. 96 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1007/BF02431539. PMID 2906446. S2CID 21417374.

- ^ Sargent PA, Sharpley AL, Williams C, Goodall EM, Cowen PJ (October 1997). "5-HT2C receptor activation decreases appetite and body weight in obese subjects". Psychopharmacology. 133 (3): 309–312. doi:10.1007/s002130050407. PMID 9361339. S2CID 7125577. Archived from the original on 2002-01-12.

- ^ Hayashi A, Suzuki M, Sasamata M, Miyata K (March 2005). "Agonist diversity in 5-HT(2C) receptor-mediated weight control in rats". Psychopharmacology. 178 (2–3): 241–249. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2019-z. PMID 15719229. S2CID 7580231.

- ^ Halford JC, Harrold JA, Boyland EJ, Lawton CL, Blundell JE (2007). "Serotonergic drugs : effects on appetite expression and use for the treatment of obesity". Drugs. 67 (1): 27–55. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767010-00004. PMID 17209663. S2CID 46972692.