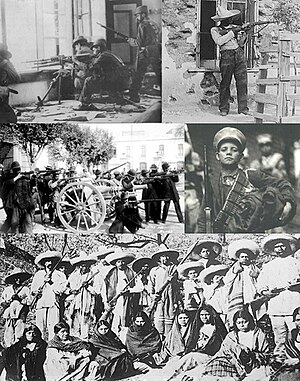

| Mexican Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From left to right and top to bottom:

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| 1910–1911: | 1910–1911: | ||||||

| 1911–1913: | 1911–1913: | ||||||

| 1913–1914: | 1913–1914: | ||||||

| 1914–1915: | 1914–1915: | ||||||

| 1915–1920: |

1915–1920

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| 1910–1911: | 1910–1911: | ||||||

1911–1913:

|

1911–1913:

| ||||||

1913–1914:

| 1913–1914: | ||||||

| 1914–1915: | 1914–1915: | ||||||

1915–1920:

|

1915–1920:

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

250,000–300,000 |

255,000–290,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

The Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Revolución mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920.[6][7][8] It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history",[9] and saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army,[10] and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940.[8][11] The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high.[12][13] The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly non-combatants.

Although the decades-long regime of President Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) was increasingly unpopular, there was no foreboding in 1910 that a revolution was about to break out.[12] The aging Díaz failed to find a controlled solution to presidential succession, resulting in a power struggle among competing elites and the middle classes, which occurred during a period of intense labor unrest, exemplified by the Cananea and Río Blanco strikes.[14] When wealthy northern landowner Francisco I. Madero challenged Díaz in the 1910 presidential election and Díaz jailed him, Madero called for an armed uprising against Díaz in the Plan of San Luis Potosí. Rebellions broke out first in Morelos and then to a much greater extent in northern Mexico. The Federal Army could not suppress the widespread uprisings, showing the military's weakness and encouraging the rebels.[15] Díaz resigned in May 1911 and went into exile, an interim government was installed until elections could be held, the Federal Army was retained, and revolutionary forces demobilized. The first phase of the Revolution was relatively bloodless and short-lived.

Madero was elected President, taking office in November 1911. He immediately faced the armed rebellion of Emiliano Zapata in Morelos, where peasants demanded rapid action on agrarian reform. Politically inexperienced, Madero's government was fragile, and further regional rebellions broke out. In February 1913, prominent army generals from the Díaz regime staged a coup d'etat in Mexico City, forcing Madero and Vice President Pino Suárez to resign. Days later, both men were assassinated by orders of the new President, Victoriano Huerta. This initiated a new and bloody phase of the Revolution, as a coalition of northerners opposed to the counter-revolutionary regime of Huerta, the Constitutionalist Army led by the Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza, entered the conflict. Zapata's forces continued their armed rebellion in Morelos. Huerta's regime lasted from February 1913 to July 1914, and the Federal Army was defeated by revolutionary armies. The revolutionary armies then fought each other, with the Constitutionalist faction under Carranza defeating the army of former ally Francisco "Pancho" Villa by the summer of 1915.

Carranza consolidated power and a new constitution was promulgated in February 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917 established universal male suffrage, promoted secularism, workers' rights, economic nationalism, and land reform, and enhanced the power of the federal government.[16] Carranza became President of Mexico in 1917, serving a term ending in 1920. He attempted to impose a civilian successor, prompting northern revolutionary generals to rebel. Carranza fled Mexico City and was killed. From 1920 to 1940, revolutionary generals held the office of president, each completing their terms (except from 1928-1934). This was a period when state power became more centralized, and revolutionary reform implemented, bringing the military under the civilian government's control.[17] The Revolution was a decade-long civil war, with new political leadership that gained power and legitimacy through their participation in revolutionary conflicts. The political party those leaders founded in 1929, which would become the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), ruled Mexico until the presidential election of 2000. When the Revolution ended, is not well defined, and even the conservative winner of the 2000 election, Vicente Fox, contended his election was heir to the 1910 democratic election of Francisco Madero, thereby claiming the heritage and legitimacy of the Revolution.[18]

- ^ "Obregón Salido Álvaro". Bicentenario de México. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Elías Calles Campuzano Plutarco". Bicentenario de México. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Finley, James P.; Reilly, Jeanne (1993). "Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: The Battle of Ambos Nogales". BYU Library. Brigham Young University. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

Mexican casualties are not known, but found among the Mexican dead were the bodies of two German agents provocateurs.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

onlinewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Rummel, Rudolph. "Table 11.1 The Mexican Democide Line 39". Statistics of Mexican Democide.

- ^ Ristow, Colby (10 February 2021), Beezley, William (ed.), "The Mexican Revolution", The Oxford Handbook of Mexican History (1 ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190699192.013.23, ISBN 978-0-19-069919-2, retrieved 18 April 2024

- ^ Johnson, Benjamin H. (20 December 2018), "The Mexican Revolution", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.491, ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5, retrieved 18 April 2024

- ^ a b Buchenau, Jürgen (3 September 2015), "The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1946", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.21, ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9, retrieved 18 April 2024

- ^ Joseph, Gilbert and Jürgen Buchenau (2013). Mexico's Once and Future Revolution. Durham: Duke University Press, 1

- ^ Lieuwen 1981.

- ^ Osten, Sarah (22 February 2018). The Mexican Revolution's Wake: The Making of a Political System, 1920–1929. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1017/9781108235570. ISBN 978-1-108-41598-9.

- ^ a b Katz 1981, p. 3.

- ^ Redinger, Matthew (2005). American Catholics and the Mexican Revolution, 1924-1936. University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 8–45. ISBN 978-0-268-04022-2.

- ^ Womack, John Jr. "The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1920". Mexico Since Independence. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991, 128.

- ^ Lieuwen 1981, p. 9.

- ^ Gentleman, Judith. "Mexico since 1910". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, 15.

- ^ Lieuwen 1981, pp. xii–xii.

- ^ Bantjes, Adrien A. "The Mexican Revolution". In A Companion to Latin American History, London: Wiley-Blackwell 2011, 330