The Mexican War of Independence (Spanish: Guerra de Independencia de México, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from the Spanish Empire. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional struggles that occurred within the same period, and can be considered a revolutionary civil war.[2] It culminated with the drafting of the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire in Mexico City on September 28, 1821, following the collapse of royal government and the military triumph of forces for independence.

Mexican independence from Spain was not an inevitable outcome of the relationship between the Spanish Empire and its most valuable overseas possession, but events in Spain had a direct impact on the outbreak of the armed insurgency in 1810 and the course of warfare through the end of the conflict. Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Spain in 1808 touched off a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule, since he had placed his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne after forcing the abdication of the Spanish monarch Charles IV. In Spain and many of its overseas possessions, the local response was to set up juntas, ruling in the name of the Bourbon monarchy. Delegates in Spain and overseas territories met in Cádiz—a small corner of the Iberian Peninsula still under Spanish control—as the Cortes of Cádiz, and drafted the Spanish Constitution of 1812. That constitution sought to create a new governing framework in the absence of the legitimate Spanish monarch. It tried to accommodate the aspirations of American-born Spaniards (criollos) for more local control and equal standing with Peninsular-born Spaniards, known locally as peninsulares. This political process had far-reaching impacts in New Spain during the independence war and beyond. Pre-existing cultural, religious, and racial divides in Mexico played a major role in not only the development of the independence movement but also the development of the conflict as it progressed.[3][4]

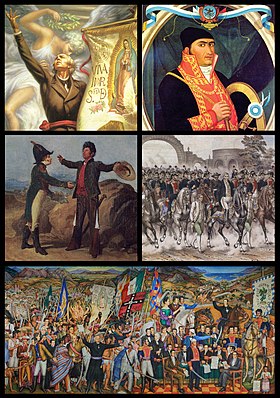

The conflict had several phases. The first uprising for independence was led by parish priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who issued the Cry of Dolores on 16 September 1810. The revolt was massive and not well organized. Hidalgo was captured by royalist forces, defrocked from the priesthood, and executed in July 1811. The second phase of the insurgency was led by Father José María Morelos, who was captured by royalist forces and executed in 1815. The insurgency devolved into guerrilla warfare, with Vicente Guerrero emerging as a leader. Neither royalists nor insurgents gained the upper hand, with military stalemate continuing until 1821, when former royalist commander Agustín de Iturbide made an alliance with Guerrero under the Plan of Iguala in 1821. They formed a unified military force rapidly bringing about the collapse of royal government and the establishment of independent Mexico. The unexpected turn of events in Mexico was prompted by events in Spain. When Spanish liberals overthrew the autocratic rule of Ferdinand VII in 1820, conservatives in New Spain saw political independence as a way to maintain their position. The unified military force entered Mexico City in triumph in September 1821 and the Spanish viceroy Juan O'Donojú signed the Treaty of Córdoba, ending Spanish rule.[5]

Following independence, the mainland of New Spain was organized as the First Mexican Empire, led by Agustín de Iturbide.[6] This ephemeral constitutional monarchy was overthrown and a federal republic was declared in 1823 and codified in the Constitution of 1824. After some Spanish reconquest attempts, including the expedition of Isidro Barradas in 1829, Spain under the rule of Isabella II recognized the independence of Mexico in 1836.[7]

- ^ "Statistics of Wars, Oppressions and Atrocities of the Nineteenth Century".

- ^ Altman, Ida et al. The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, pp. 341–358.

- ^ Hamnett, Brian (1999). A Concise History of Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 147–186.

- ^ Archer, Christon (2007). The Birth of Modern Mexico, 1780–1824. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5602-7.

- ^ Archer, Christon I. "Wars of Independence" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 1595–1601.

- ^ Mexico independiente, 1821–1851 Archived 22 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Monografias, 1996; accessed 21 December 2018.

- ^ http://pares.mcu.es/Bicentenarios/portal/reconocimientoEspana.html Archived 17 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine accessed 21 December 2018.