In animation and film, "Mickey Mousing" (synchronized, mirrored, or parallel scoring) is a film technique that syncs the accompanying music with the actions on screen, "Matching movement to music",[2] or "The exact segmentation of the music analogue to the picture."[3][a] The term comes from the early and mid-production Walt Disney films, where the music almost completely works to mimic the animated motions of the characters. Mickey Mousing may use music to "reinforce an action by mimicking its rhythm exactly. ... Frequently used in the 1930s and 1940s, especially by Max Steiner,[b] it is somewhat out of favor today, at least in serious films, because of overuse. However, it can still be effective if used imaginatively".[11] Mickey Mousing and synchronicity help structure the viewing experience, to indicate how much events should impact the viewer, and to provide information not present on screen.[12] The technique "enable[s] the music to be seen to 'participate' in the action and for it to be quickly and formatively interpreted ... and [to] also intensify the experience of the scene for the spectator."[6] Mickey Mousing may also create unintentional humor,[5][13] and be used in parody or self-reference.

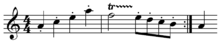

It is often not the music that is synced to the animated action, but the other way around. This is especially so when the music is a classical or other well-known piece. In such cases, the music for the animation is pre-recorded, and an animator will have an exposure sheet with the beats marked on it, frame by frame, and can time the movements accordingly. In the 1940 film Fantasia, the musical piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice by Paul Dukas, composed in the 1890s, contains a fragment that is used to accompany the actions of Mickey Mouse himself. At one point Mickey, as the apprentice, seizes an axe and chops an enchanted broom to pieces so that it will stop carrying water to a pit. The visual action is synchronized exactly to crashing chords in the music.

- ^ Goldmark, D. (2011) "Sounds Funny/Funny Sounds" in D. Goldmark and C. Keil (eds). Funny Pictures: Animation and comedy in studio-era Hollywood pp 260-261. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California. ISBN 9780520950122.

- ^ Bordwell (2008), p.276, quoted in Rauscher, Andreas (2012). "Scoring Play: Soundtracks and Video Game Genres", Music and Game: Perspectives on a Popular Alliance, p.98. Moormann, Peter; ed. ISBN 9783531189130.

- ^ a b Wegele, Peter (2014). Max Steiner: Composing, Casablanca, and the Golden Age of Film Music, p.37. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442231146.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MacDonaldwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Stevens, Meghan (2009). Music and Image in Concert, p.94. Music and Media, Syndney. ISBN 9780980732603.

- ^ a b Edmondson, Jacqueline, ed. (2013). Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories That Shaped Our Culture, p.199. ABC-CLIO: Greenwood. ISBN 9780313393488.

- ^ Lebo, Harlan (1992). Casablanca: Behind the Scenes, p.178. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671769819.

- ^ Helvering, David Allen (July 2007). "Functions of Dialogue Underscoring in American Feature Film", p.177. The University of Iowa. ISBN 9780549235040.

- ^ Kalinak (1992), p.86.

- ^ Helvering (2007), p.103n28.

- ^ Newlin, Dika (1977). "Music for the Flickering Image – American Film Scores", Music Educators Journal, Vol. 64, No. 1. (September 1977), pp. 24–35.pdf

- ^ Helvering (2007), pp. 178–180. Would viewers still have, "empathized with Kong if Steiner had not used Mickey Mousing to show Kong getting hurt when poked with knives or shot with bullets"? p.22.

- ^ Rauscher (2012), p.98.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).