This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

| Modern Standard Arabic | |

|---|---|

| العربية الفصحى الحديثة al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā al-Ḥadītha[a] | |

al-ʻArabīyah written in Arabic (Naskh script) | |

| Pronunciation | /al ʕaraˈbijja lˈfusˤħaː/, see variations[b] |

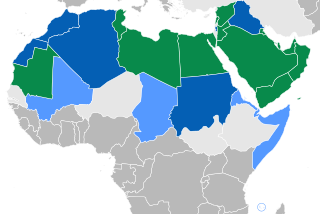

| Region | Arab world Middle East and North Africa |

| Users | 330 million (2023)[1] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms | |

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | List

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | arb |

arb-mod | |

| Glottolog | stan1318 |

Sole official language

Co-official language, majority Arabophone

Co-official language, minority Arabophone | |

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA)[3] is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[4][5] and in some usages also the variety of spoken Arabic that approximates this written standard.[6] MSA is the language used in literature, academia, print and mass media, law and legislation, though it is generally not spoken as a first language, similar to Contemporary Latin.[5] It is a pluricentric standard language taught throughout the Arab world in formal education, differing significantly from many vernacular varieties of Arabic that are commonly spoken as mother tongues in the area; these are only partially mutually intelligible with both MSA and with each other depending on their proximity in the Arabic dialect continuum.

Many linguists consider MSA to be distinct from Classical Arabic (CA; اللغة العربية الفصحى التراثية al-Lughah al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā at-Turāthīyah) – the written language prior to the mid-19th century – although there is no agreed moment at which CA turned into MSA.[7] There are also no agreed set of linguistic criteria which distinguish CA from MSA;[7] however, MSA differs most markedly in that it either synthesizes words from Arabic roots (such as سيارة car or باخرة steamship) or adapts words from foreign languages (such as ورشة workshop or إنترنت Internet) to describe industrial and post-industrial life.

Native speakers of Arabic generally do not distinguish between "Modern Standard Arabic" and "Classical Arabic" as separate languages; they refer to both as Fuṣḥā Arabic or al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā (العربية الفصحى), meaning "the most eloquent Arabic".[8] They consider the two forms to be two historical periods of one language. When the distinction is made, they do refer to MSA as Fuṣḥā al-ʻAṣr (فصحى العصر), meaning "Contemporary Fuṣḥā" or "Modern Fuṣḥā", and to CA as Fuṣḥā at-Turāth (فصحى التراث), meaning "Hereditary Fuṣḥā" or "Historical Fuṣḥā".[8]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Modern Standard Arabic at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "Basic Law: Israel - The Nation State of the Jewish People" (PDF). Knesset. 19 July 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Gully, Adrian; Carter, Mike; Badawi, Elsaid (29 July 2015). Modern Written Arabic: A Comprehensive Grammar (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-0415667494.

- ^ Giolfo and, Manuela E.B.; Sinatora, Francesco L. (27 April 2018), Keskin, Tugrul (ed.), "Orientalism and Neo-Orientalism: Arabic Representations and the Study of Arabic", Middle East Studies after September 11, BRILL, pp. 81–99, doi:10.1163/9789004359901_005, ISBN 978-90-04-28153-0, retrieved 14 June 2023

- ^ a b Kamusella, Tomasz (2017). "The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity?" (PDF). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. 11 (2): 117–145. doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006. S2CID 158624482.

- ^ Alhawary, Mohammad. Modern Standard Arabic. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p. 24.

- ^ a b Holes, C.; Allen, R. (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Georgetown classics in Arabic language and linguistics. Georgetown University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-58901-022-2.

…there is no chronological point at which CLA turned into MSA, still less any agreed set of linguistic criteria that could differentiate the two. MSA is merely a handy label used in western scholarship to denote the written language from about the middle of the nineteenth century, when concerted efforts began to modernize it lexically and phraseologically. Most western scholars refer to the formal written language before that date, and par excellence before the eclipse of Arab political power in the fifteenth century, as "Classical Arabic".

- ^ a b Alaa Elgibali and El-Said M. Badawi. Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said M. Badawi, 1996. Page 105.