This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2021) |

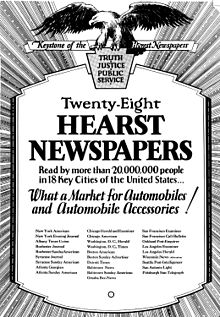

Monopolies of knowledge arise when the ruling class maintains political power through control of key communications technologies.[2] The Canadian economic historian Harold Innis developed the concept of monopolies of knowledge in his later writings on communications theories.[3]

An example is given of ancient Egypt, where a complex writing system conferred a monopoly of knowledge on literate priests and scribes. Mastering the art of writing and reading required long periods of apprenticeship and instruction, confining knowledge to this powerful class.[4] It is suggested that monopolies of knowledge gradually suppress new ways of thinking. Entrenched hierarchies become increasingly rigid and out of touch with social realities. Challenges to elite power are often likely to arise on the margins of society. The arts, for example, are often seen as a means of escape from the sterility of conformist thought.[5]

In his later writings, Innis argued that industrialization and mass media had led to the mechanization of a culture in which more personal forms of oral communication were radically devalued.[6] "Reading is quicker than listening," Innis wrote in 1948. "The printing press and the radio address the world instead of the individual."[7]

We can look at the Internet as being a factor in creating knowledge monopolies. Those who have the skills to use the technology have the power to choose what information is communicated. The significance of the Internet in the creation of these monopolies, in more recent years, has been somewhat diminished due to increased knowledge and awareness of how to use the technology. At the same time, the ever-increasing complexity of digital technologies strengthens monopolies of knowledge, according to the New York Times:

[T]he Pentagon has commissioned military contractors to develop a highly classified replica of the Internet of the future. The goal is to simulate what it would take for adversaries to shut down the country’s power stations, telecommunications and aviation systems, or freeze the financial markets — in an effort to build better defenses against such attacks, as well as a new generation of online weapons.[8]

Wherever new media arise, so too do monopolies of knowledge concerning how to use the technologies to reinforce the power and control of elite groups.

- ^ Innis, Harold. (1951) The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 179-180.

- ^ Watson, Alexander John. (2006). Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p.357.

- ^ Heyer, Paul. (2003) Harold Innis. Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., p.76.

- ^ Innis, Harold. (2007) Empire and Communications. Toronto: Dundurn Press, p.44.

- ^ Innis, Harold. (1980) The Idea File of Harold Adams Innis, introduced and edited by William Christian. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp.xii-xiii.

- ^ Heyer, pp.80-81.

- ^ Innis (Bias), p.191.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Markoff, John; Shanker, Thom (27 April 2009). "In Cyberweapons Race, Questions Linger Over U.S. Offensive Capability". The New York Times.