In music, a mordent is an ornament indicating that the note is to be played with a single rapid alternation with the note above or below. Like trills, they can be chromatically modified by a small flat, sharp or natural accidental. The term entered English musical terminology at the beginning of the 19th century, from the German Mordent and its Italian etymon, mordente, both used in the 18th century to describe this musical figure. The word ultimately is derived from Latin mordere 'to bite'.

The mordent is thought of as a rapid single alternation between an indicated note, the note above (the upper mordent) or below (the lower mordent) and the indicated note again.

In musical notation, the upper mordent is indicated by a short squiggle; the lower mordent is the same with a short vertical line through it:[1]

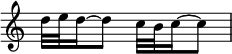

As with the trill, the exact speed with which the mordent is performed will vary according to the tempo of the piece, but at a moderate tempo the above might be executed as follows:[1]

The precise meaning of mordent has changed over the years. In the Baroque period, a mordent was a lower mordent and an upper mordent was a pralltriller or schneller. In the 19th century, however, the name mordent was generally applied to what is now called the upper mordent, and the lower mordent became known as an inverted mordent.[2]

In other languages the situation is different: for example in German Pralltriller and Mordent are still the upper and lower mordents respectively. This ornament in French, and sometimes in German, is spelled mordant.

Although mordents are now thought of as just a single alternation between notes, in the Baroque period it appears that a Mordent may have sometimes been executed with more than one alternation between the indicated note and the note below, making it a sort of inverted trill.

Also, mordents of all sorts might typically, in some periods, begin with an extra unessential note (the lesser, added note), rather than with the principal note as shown in the examples here. The same applies to trills, which in Baroque and Classical times would typically begin with the added, upper note. Practice, notation, and nomenclature vary widely for all of these ornaments, and this article as a whole addresses an approximate nineteenth-century standard.

The slide can be written using a symbol similar to that of the mordent, but placed to the left of the principal note, rather than above it.

- ^ a b Harnum, Jonathan (2006). Sound the Trumpet: How to Blow Your Own Horn. Sol Ut Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1450590181.

- ^ Taylor, Eric (1989). The AB Guide to Music Theory. London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. p. 93. ISBN 1-85472-446-0.