Republic of the Union of Myanmar

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: ကမ္ဘာမကျေ Kaba Ma Kyei "Till the End of the World" | |

| Capital | Naypyidaw[b] 21°00′N 96°00′E / 21.000°N 96.000°E |

| Largest city | Yangon[a] |

| Official language | Burmese |

| Recognised regional languages[1] | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | [7] |

| Government | Unitary assembly-independent republic under a military junta |

| Min Aung Hlaing | |

| Soe Win[e] | |

| Legislature | State Administration Council |

| Formation | |

| 23 December 849 | |

| 16 October 1510 | |

| 29 February 1752 | |

| 1 January 1886 | |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 4 January 1948 |

| 2 March 1962 | |

| 18 September 1988 | |

| 31 January 2011 | |

| 1 February 2021 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 676,579 km2 (261,229 sq mi) (39th) |

• Water (%) | 3.06 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 55,770,232[11] (26th) |

• Density | 196.8/sq mi (76.0/km2) (125th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | medium inequality (106th) |

| HDI (2022) | medium (144th) |

| Currency | Kyat (K) (MMK) |

| Time zone | UTC+06:30 (MMT) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +95 |

| ISO 3166 code | MM |

| Internet TLD | .mm |

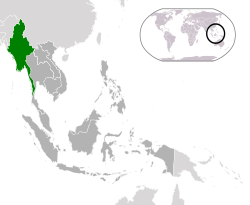

Myanmar,[f] officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar[g] and also rendered Burma (the official English form until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has a population of about 55 million.[18] It is bordered by India to its west, Bangladesh to its southwest, China to its northeast, Laos and Thailand to its east and southeast, and the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal to its south and southwest. The country's capital city is Naypyidaw, and its largest city is Yangon (formerly Rangoon).[19]

Early civilisations in the area included the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu city-states in Upper Myanmar and the Mon kingdoms in Lower Myanmar.[20] In the 9th century, the Bamar people entered the upper Irrawaddy valley, and following the establishment of the Pagan Kingdom in the 1050s, the Burmese language, culture, and Theravada Buddhism slowly became dominant in the country. The Pagan Kingdom fell to Mongol invasions, and several warring states emerged. In the 16th century, reunified by the Taungoo dynasty, the country became the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia for a short period.[21] The early 19th-century Konbaung dynasty ruled over an area that included modern Myanmar and briefly controlled Assam, the Lushai Hills, and Manipur as well. The British East India Company seized control of the administration of Myanmar after three Anglo-Burmese Wars in the 19th century, and the country became a British colony. After a brief Japanese occupation, Myanmar was reconquered by the Allies. On 4 January 1948, Myanmar declared independence under the terms of the Burma Independence Act 1947.

Myanmar's post-independence history has been checkered by continuing unrest and conflict to this day. The coup d'état in 1962 resulted in a military dictatorship under the Burma Socialist Programme Party. On 8 August 1988, the 8888 Uprising then resulted in a nominal transition to a multi-party system two years later, but the country's post-uprising military council refused to cede power, and has continued to rule the country through to the present. The country remains riven by ethnic strife among its myriad ethnic groups and has one of the world's longest-running ongoing civil wars. The United Nations and several other organisations have reported consistent and systemic human rights violations in the country.[22] In 2011, the military junta was officially dissolved following a 2010 general election, and a nominally civilian government was installed. Aung San Suu Kyi and political prisoners were released and the 2015 Myanmar general election was held, leading to improved foreign relations and eased economic sanctions,[23] although the country's treatment of its ethnic minorities, particularly in connection with the Rohingya conflict, continued to be a source of international tension and consternation.[24] Following the 2020 Myanmar general election, in which Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won a clear majority in both houses, the Burmese military (Tatmadaw) again seized power in a coup d'état.[25] The coup, which was widely condemned by the international community, led to continuous ongoing widespread protests in Myanmar and has been marked by violent political repression by the military, as well as a larger outbreak of the civil war.[26] The military also arrested Aung San Suu Kyi in order to remove her from public life, and charged her with crimes ranging from corruption to violation of COVID-19 protocols; all of the charges against her are "politically motivated" according to independent observers.[27]

Myanmar is a member of the East Asia Summit, Non-Aligned Movement, ASEAN, and BIMSTEC, but it is not a member of the Commonwealth of Nations despite once being part of the British Empire. Myanmar is a Dialogue Partner of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The country is very rich in natural resources, such as jade, gems, oil, natural gas, teak and other minerals, as well as also endowed with renewable energy, having the highest solar power potential compared to other countries of the Great Mekong Subregion.[28] However, Myanmar has long suffered from instability, factional violence, corruption, poor infrastructure, as well as a long history of colonial exploitation with little regard to human development.[29] In 2013, its GDP (nominal) stood at US$56.7 billion and its GDP (PPP) at US$221.5 billion.[30] The income gap in Myanmar is among the widest in the world, as a large proportion of the economy is controlled by cronies of the military junta.[31] Myanmar is one of the least developed countries; as of 2020, according to the Human Development Index, it ranks 147 out of 189 countries in terms of human development, the lowest in Southeast Asia.[32] Since 2021, more than 600,000 people were displaced across Myanmar due to the surge in violence post-coup, with more than 3 million people in dire need of humanitarian assistance.[33]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "Myanmar | Ethnologue Free". Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Overview of Myanmar's diversity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "ISP Myanmar talk shows". 15 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "PonYate ethnic population dashboard". Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Myanmar's Constitution of 2008" (PDF). constituteproject.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census- The Union Report: Religion" (PDF). myanmar.unfpa.org. Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population MYANMAR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "ACT Health Community Profile, pg. 1" (PDF). Multicultural Health Policy Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "Myanmar Junta Reshuffles Governing Body". The Irrawaddy. 2 February 2023. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar reshuffle of generals suggests 'instability,' experts say". Radio Free Asia. 26 September 2023. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar Junta Leader Reshuffles Cabinet Days After Extending Emergency Rule". The Irrawaddy. 4 August 2023. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "The 2014 Myanmar Populations and Housing Census" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/MMR.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/MMR.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/MMR.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. p. 289. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Myanmar Population 2024 (Live)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ "Burma". The World Factbook. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. 8 August 2023. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ O'Reilly, Dougald JW (2007). Early civilizations of Southeast Asia. United Kingdom: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0279-8.

- ^ Lieberman, p. 152

- ^ "Burma". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

"Myanmar Human Rights". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

"World Report 2012: Burma". Human Rights Watch. 22 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013. - ^ Madhani, Aamer (16 November 2012). "Obama administration eases Burma sanctions before visit". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

Fuller, Thomas; Geitner, Paul (23 April 2012). "European Union Suspends Most Myanmar Sanctions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. - ^ Greenwood, Faine (27 May 2013). "The 8 Stages of Genocide Against Burma's Rohingya | UN DispatchUN Dispatch". Undispatch.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

"EU welcomes "measured" Myanmar response to rioting". Reuters. 11 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

"Q&A: Communal violence in Burma". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2013. - ^ "Myanmar military takes control of country after detaining Aung San Suu Kyi". BBC News. 1 February 2021. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Wee, Sui-Lee (5 December 2021). "Fatalities Reported After Military Truck Rams Protesters in Myanmar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca (6 December 2021). "Myanmar's junta condemned over guilty verdicts in Aung San Suu Kyi trial". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Vakulchuk, Roman; Kyaw Kyaw Hlaing; Edward Ziwa Naing; Indra Overland; Beni Suryadi and Sanjayan Velautham (2017). Myanmar's Attractiveness for Investment in the Energy Sector. A Comparative International Perspective. Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of Strategic and International Studies (MISIS) Report. p. 8.

- ^ Wong, John (March 1997). "Why Has Myanmar not Developed Like East Asia?". ASEAN Economic Bulletin. 13 (3): 344–358. doi:10.1355/AE13-3E (inactive 22 November 2024). ISSN 0217-4472. JSTOR 25773443. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Burma (Myanmar)". World Economic Outlook Database. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Eleven Media (4 September 2013). "Income Gap 'world's widest'". The Nation. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

McCornac, Dennis (22 October 2013). "Income inequality in Burma". Democratic Voice of Burma. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014. - ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Issue Brief: Dire Consequences: Addressing the Humanitarian Fallout from Myanmar's Coup - Myanmar". ReliefWeb. 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.