| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3,3′,4′,5,5′,7-Hexahydroxyflavone

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

3,5,7-Trihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

Cannabiscetin

Myricetol Myricitin | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.695 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

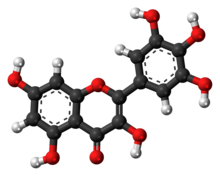

| C15H10O8 | |

| Molar mass | 318.237 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.912 g/mL |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Myricetin is a member of the flavonoid class of polyphenolic compounds, with antioxidant properties.[1] Common dietary sources[2] include vegetables (including tomatoes), fruits (including oranges), nuts, berries, tea,[3] and red wine.[4]

Myricetin is structurally similar to fisetin, luteolin, and quercetin and is reported to have many of the same functions as these other members of the flavonol class of flavonoids.[3] Reported average intake of myricetin per day varies depending on diet, but has been shown in the Netherlands to average 23 mg/day.[5]

Myricetin is produced from the parent compound taxifolin through the (+)-dihydromyricetin intermediate and can be further processed to form laricitrin and then syringetin, both members of the flavonol class of flavonoids.[6] Dihydromyricetin is frequently sold as a supplement and has controversial function as a partial GABAA receptor potentiator and treatment in Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). Myricetin can alternatively be produced directly from kaempferol, which is another flavonol.[6]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ongwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Holland, Thomas M.; Agarwal, Puja; Wang, Yamin; Leurgans, Sue E.; Bennett, David A.; Booth, Sarah L.; Morris, Martha Clare (2020-01-29). "Dietary flavonols and risk of Alzheimer dementia". Neurology. 94 (16): e1749–e1756. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008981. ISSN 0028-3878. PMC 7282875. PMID 31996451.

- ^ a b Ross JA, Kasum CM (July 2002). "Dietary Flavonoids: Bioavailability, Metabolic Effects, and Safety". Annual Review of Nutrition. 22: 19–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957. PMID 12055336.

- ^ Basli A, Soulet S, Chaher N, Merillon JM, Chibane M, Monti JP, Richard T (July 2012). "Wine polyphenols: potential agents in neuroprotection". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012: 805762. doi:10.1155/2012/805762. PMC 3399511. PMID 22829964.

- ^ Hollman PC, Katan MB (Dec 1999). "Health effects and bioavailability of dietary flavonols". Free Radical Research. 31 Suppl: Suppl S75–80. doi:10.1080/10715769900301351. PMID 10694044.

- ^ a b Flamini R, Mattivi F, De Rosso M, Arapitas P, Bavaresco L (Sep 2013). "Advanced knowledge of three important classes of grape phenolics: anthocyanins, stilbenes and flavonols". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (10): 19651–69. doi:10.3390/ijms141019651. PMC 3821578. PMID 24084717.