| New York City Draft Riots of 1863 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Opposition to the American Civil War | |||

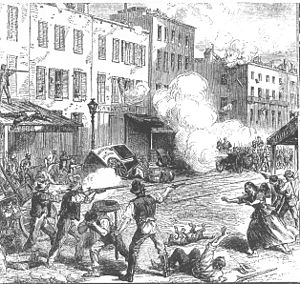

An illustration in The Illustrated London News depicting armed rioters clashing with Union Army soldiers in New York City | |||

| Date | July 13–16, 1863 | ||

| Location | Manhattan, New York City, U.S. | ||

| Caused by | Civil War conscription; racism; competition for jobs between black and white people. | ||

| Resulted in | Riots ultimately suppressed | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 119–120[1][2] | ||

| Injuries | 2,000 | ||

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week,[3] were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil urban disturbance in American history.[4] According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" within the city's Irish community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."[5]

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city.

The protests turned into a race riot against African-Americans by Irish rioters. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."[6]

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was burned to the ground.[7] The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.[7]

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1982), Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 360, ISBN 978-0-394-52469-6

- ^ "VNY: Draft Riots Aftermath". Vny.cuny.edu. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, David M. (1863). The Draft Riots in New York, July 1863: The Metropolitan Police, Their Services During Riot. Baker & Godwin. pp. 5–6, 12.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. The New American Nation. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-06-093716-5. (updated ed. 2014, ISBN 978-0062354518).

- ^ Toby Joyce, "The New York Draft Riots of 1863: An Irish Civil War?" History Ireland (March 2003) 11#2, pp 22–27.

- ^ "Maj. Gen. John E. Wool Official Reports for the New York Draft Riots". Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War blogsite. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863. University of Chicago Press. pp. 279–88. ISBN 0226317757.