The Nicene Creed,[a] also called the Creed of Constantinople,[1] is the defining statement of belief of Nicene Christianity[2][3] and in those Christian denominations that adhere to it.

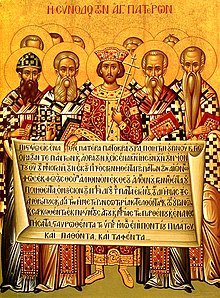

The original Nicene Creed was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. According to the traditional view, forwarded by the Council of Chalcedon of 451, the Creed was amended in 381 by the First Council of Constantinople as "consonant to the holy and great Synod of Nice."[4] However, many scholars comment on these ancient Councils saying "there is a failure of evidence" for this position since no one between the years of 381–451 thought of it in this light.[5] Further, a creed "almost identical in form" was used as early as 374 by St. Epiphanius of Salamis.[6] Nonetheless, the amended form is presently referred to as the Nicene Creed or the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. J.N.D. Kelly, who stands among historians as an authority on creedal statements, disagrees with the aforementioned assessment. He argues that since Constantinople I was not considered ecumenical until Chalcedon in 451, the absence of documentation during this period does not logically necessitate rejecting it as an expansion of the original Nicene Creed of 325.[6]

The Nicene Creed is part of the profession of faith required of those undertaking important functions within the Orthodox, Catholic and Lutheran Churches.[7][8][9] Nicene Christianity regards Jesus as divine and "begotten of the Father".[10] Various conflicting theological views existed before the fourth century and these spurred the ecumenical councils which eventually developed the Nicene Creed, and various non-Nicene beliefs have emerged and re-emerged since the fourth century, all of which are considered heresies[11] by adherents of Nicene Christianity.

In Western Christianity, the Nicene Creed is in use alongside the less widespread Apostles' Creed,[12][13][14] and Athanasian Creed.[15][8] However, part of it can be found as an "Authorized Affirmation of Faith" in the main volume of the Common Worship liturgy of the Church of England published in 2000.[16][17] In musical settings, particularly when sung in Latin, this creed is usually referred to by its first word, Credo. On Sundays and solemnities, one of these two creeds is recited in the Roman Rite Mass after the homily. In the Byzantine Rite, the Nicene Creed is sung or recited at the Divine Liturgy, immediately preceding the Anaphora (eucharistic prayer) is also recited daily at compline.[18][19]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Cone, Steven D.; Rea, Robert F. (2019). A Global Church History: The Great Tradition through Cultures, Continents and Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. lxxx. ISBN 978-0-567-67305-3.

- ^ World Encyclopaedia of Interfaith Studies: World religions. Jnanada Prakashan. 2009. ISBN 978-81-7139-280-3.

In the most common sense, "mainstream" refers to Nicene Christianity, or rather the traditions which continue to claim adherence to the Nicene Creed.

- ^ Seitz, Christopher R. (2001). Nicene Christianity: The Future for a New Ecumenism. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1-84227-154-4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Council of Chalcedon". New Advent. Session II.

- ^ Bright, William (1882). Notes on the Canons of the First Four General Councils. Oxford : Clarendon Press. pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b Davis, Leo Donald (1988). The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology. Theology and Life Series 21. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier. pp. 121–124. ISBN 0-8146-5616-1.

- ^ "Profession of Faith". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b "The Three Ecumenical or Universal Creeds" (PDF). Concordia University Ann Arbor. p. 1. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Meister, Chad; Copan, Paul (2010). Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-18000-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Britannicawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^

Jenner, Henry (1908). "Liturgical Use of Creeds". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Jenner, Henry (1908). "Liturgical Use of Creeds". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "The Nicene Creed - Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese". Antiochian.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "The Orthodox Faith – Volume I – Doctrine and Scripture – The Symbol of Faith – Nicene Creed". oca.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Weinandy, Thomas G.; Keating, Daniel A. (1 November 2017). Athanasius and His Legacy: Trinitarian-Incarnational Soteriology and Its Reception. Fortress Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-5064-0629-9.

In the Lutheran Book of Concord (1580), the Quicunque is given equal honor with the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds; the Belgic Confession of the Reformed church (1566) accords it authoritative status; and the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles declare it as one of the creeds that ought to be received and believed.

- ^ Morin 1911

- ^ Kantorowicz 1957, p. 17

- ^ [1] Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Archbishop Averky Liturgics – The Small Compline", Retrieved 14 April 2013

- ^ [2] Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Archbishop Averky Liturgics – The Symbol of Faith", Retrieved 14 April 2013