| Northern American English | |

|---|---|

| Northern U.S. English | |

| Region | Northern United States |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | nort3316 |

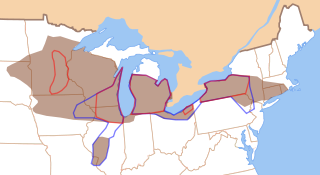

21st century research unites the brown region of this map as a Northern U.S. superdialect region. Notice that the Northwest and much of New England are not included. | |

Northern American English or Northern U.S. English (also, Northern AmE) is a class of historically related American English dialects, spoken by predominantly white Americans,[1] in much of the Great Lakes region and some of the Northeast region within the United States. The North as a superdialect region is best documented by the 2006 Atlas of North American English (ANAE) in the greater metropolitan areas of Connecticut, Western Massachusetts, Western and Central New York, Northwestern New Jersey, Northeastern Pennsylvania, Northern Ohio, Northern Indiana, Northern Illinois, Northeastern Nebraska, and Eastern South Dakota, plus among certain demographics or areas within Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Vermont, and New York's Hudson Valley.[2] The ANAE describes that the North, at its core, consists of the Inland Northern dialect (in the eastern Great Lakes region) and Southwestern New England dialect.[3]

The ANAE argues that, though geographically located in the Northern United States, current-day New York City, Eastern New England, Northwestern U.S., and some Upper Midwestern accents do not fit under the Northern U.S. accent spectrum, or only marginally. Each has one or more phonological characteristics that disqualifies them or, for the latter two, exhibit too much internal variation to classify definitively. Meanwhile, Central and Western Canadian English is presumed to have originated, but branched off, from Northern U.S. English within the past two or three centuries.[4][5]

Most broadly, the ANAE classifies Northern U.S. accents as rhotic, distinguished from Southern U.S. accents by retaining /aɪ/ as a diphthong (unlike the South, which commonly monophthongizes this sound) and from Western U.S. and Canadian accents by mostly preserving the distinction between the /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ sounds in words like cot versus caught[6] (though the latter feature appears to be changing among the younger generations).

In the very early 20th century, a generic Northern U.S. accent was the basis for the term "General American", though regional accents have now since developed in some areas of the North.[7][8]

- ^ Purnell, Thomas; Eric Raimy; and Joseph Salmons (eds.) (2013). Wisconsin talk: Linguistic diversity in the Badger State. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 109.

- ^ Labov, William; Sharon Ash, Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 134.

- ^ Labov, William; Sharon Ash, Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 148.

- ^ "Canadian English". Brinton, Laurel J., and Fee, Marjery, ed. (2005). Ch. 12. in The Cambridge history of the English language. Volume VI: English in North America., Algeo, John, ed., pp. 422–440. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-521-26479-0, 978-0-521-26479-2. On p. 422: "It is now generally agreed that Canadian English originated as a variant of northern American English (the speech of New England, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania)".

- ^ "Canadian English". McArthur, T., ed. (2005). Concise Oxford companion to the English language, pp. 96–102. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280637-8. On p. 97: "Because CanE and AmE are so alike, some scholars have argued that in linguistic terms Canadian English is no more or less than a variety of (Northern) American English".

- ^ Labov, William; Sharon Ash, Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 133.

- ^ Labov et al., p. 190.

- ^ "Talking the Tawk", The New Yorker