Oregon Country | |

|---|---|

| 1818–1846 | |

|

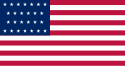

American and Hudson's Bay Company flags were used. | |

| |

| Capital |

|

| Government | |

• (British; 1818–1822) | Governor Joseph Berens of Hudson's Bay Company |

• (British; 1822–1846) | Governor John Pelly of Hudson's Bay Company |

• (U.S.; 1841–1843) | Supreme Judge Ira Babcock |

• (U.S.; 1843–1845) | Executive Committee |

• (U.S.; 1845–1846) | Governor George Abernethy |

| History | |

• Established | October 20, 1818 |

• North West Company merges with Hudson's Bay Company | July 1821 |

• Fort Vancouver built | 1824 |

• Oregon City built | 1829 |

| February 18, 1841 | |

| May 2, 1843 | |

| July 5, 1843 | |

• George Abernethy becomes Governor | June 3, 1845 |

| June 15, 1846 | |

| Currency | Beaver skin |

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcated by the Treaty of 1818, consisted of the land north of 42° N latitude, south of 54°40′ N latitude, and west of the Rocky Mountains down to the Pacific Ocean and east to the Continental Divide. Article III of the 1818 treaty gave joint control to both nations for ten years, allowed land to be claimed, and guaranteed free navigation to all mercantile trade. However, both countries disputed the terms of the international treaty. Oregon Country was the American name, while the British used Columbia District for the region.[1]

British and French Canadian fur traders had entered Oregon Country prior to 1810 before the arrival of American settlers from the mid-1830s onwards, which led to the foundation of the Provisional Government of Oregon. Its coastal areas north of the Columbia River were frequented by ships from all nations engaged in the maritime fur trade, with many vessels between the 1790s and 1810s coming from Boston. The Hudson's Bay Company, whose Columbia Department comprised most of the Oregon Country and north into New Caledonia and beyond 54°40′ N, with operations reaching tributaries of the Yukon River, managed and represented British interests in the region.[2]

After the dispute became an election issue in the 1844 U.S. presidential election, the United Kingdom and the United States agreed to settle the problem with the Oregon Treaty in 1846. It established the British-American boundary at the 49th parallel (except Vancouver Island).[3] With the end of joint occupancy, the region south of the 49th parallel became Oregon Territory in the United States while the northern portion became part of the British colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. The area, which once encompassed Oregon Country, now lies within the present-day borders of the Canadian province of British Columbia and the entirety of the U.S. states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as parts of Montana and Wyoming.

Throughout this period, the Oregon Country was inhabited by numerous independent American Indian peoples, who received no recognition by the British or American governments in the eventual disposition of the territory. Indian traders nevertheless played a critical role in the ongoing fur trade that still formed the Oregon Country's primary economic activity until mid-century, and the language of the Chinook nation of the lower Columbia river (Chinook jargon) formed the lingua franca between Indians and the small European population during and after the 1818-46 period.[4] This was the last period in which the Oregon Country's Indian nations retained a sizeable majority in their land, prior to the rapid and devastating arrival of European diseases in the 1860s, and were able to maintain relative economic independence thanks to the necessity of their hunting skills in the fur trade. The eventual partition of the Oregon Country into national domains by the two colonial powers, increasing settlement, and the drastic decline of the fur trade due to diminishing supply all contributed to catastrophic decline in Indian population after 1846, and the arbitrary seizure of their land over the following two decades in the interests of newly arrived settlers.[5]

- ^ Meinig, D. W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793–1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3.

- ^ "Britain and the United States agree on the 49th parallel as the main Pacific Northwest boundary in the Treaty of Oregon on June 15, 1846". History Link. July 13, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Ray, Verne F. (1937). "The Historical Position of the Lower Chinook in the Native Culture of the Northwest". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 28 (4): 363–372. ISSN 0030-8803.

- ^ Ray, Verne F. (1937). "The Historical Position of the Lower Chinook in the Native Culture of the Northwest". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 28 (4): 363–372. ISSN 0030-8803.