The ruins of Palmyra in 2010 | |

| Alternative name | Tadmor |

|---|---|

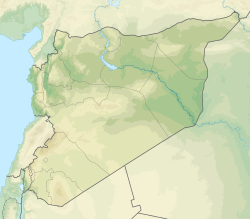

| Location | Tadmur, Homs Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Syrian Desert |

| Coordinates | 34°33′05″N 38°16′05″E / 34.55139°N 38.26806°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Part of | Palmyrene Empire |

| Area | 80 ha (200 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd millennium BC |

| Abandoned | 1932 |

| Periods | Middle Bronze Age to Modern |

| Cultures | Aramaic, Arabic, Greco-Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Management | Syrian Ministry of Culture |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Site of Palmyra |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 1980 (4th Session) |

| Reference no. | 23 |

| Region | Arab states |

| Endangered | 2013–present |

Palmyra (/pælˈmaɪrə/ pal-MY-rə; Palmyrene: 𐡶𐡣𐡬𐡥𐡴 (![]() ), romanized: Tadmor; Arabic: تَدْمُر, romanized: Tadmur) is an ancient city in the eastern part of the Levant, now in the center of modern Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second millennium BC. Palmyra changed hands on a number of occasions between different empires before becoming a subject of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

), romanized: Tadmor; Arabic: تَدْمُر, romanized: Tadmur) is an ancient city in the eastern part of the Levant, now in the center of modern Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second millennium BC. Palmyra changed hands on a number of occasions between different empires before becoming a subject of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

The city grew wealthy from trade caravans; the Palmyrenes became renowned as merchants who established colonies along the Silk Road and operated throughout the Roman Empire. Palmyra's wealth enabled the construction of monumental projects, such as the Great Colonnade, the Temple of Bel, and the distinctive tower tombs. Ethnically, the Palmyrenes combined elements of Amorites, Arameans, and Arabs. Socially structured around kinship and clans, Palmyra's inhabitants spoke Palmyrene Aramaic, a variety of Western Middle Aramaic, while using Koine Greek for commercial and diplomatic purposes. The Hellenistic period of West Asia influenced the culture of Palmyra, which produced distinctive art and architecture that combined different Mediterranean traditions. The city's inhabitants worshiped local Semitic, Mesopotamian, and Arab deities.

By the third century, Palmyra had become a prosperous regional center. It reached the apex of its power in the 260s, when the Palmyrene King Odaenathus defeated the Sasanian emperor Shapur I. The king was succeeded by queen regent Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the Palmyrene Empire. In 273, Roman emperor Aurelian destroyed the city, which was later restored by Diocletian at a reduced size. The Palmyrenes converted to Christianity during the fourth century and to Islam in the centuries following the conquest by the 7th-century Rashidun Caliphate, after which the Palmyrene and Greek languages were replaced by Arabic.

Before AD 273, Palmyra enjoyed autonomy and was attached to the Roman province of Syria, having its political organization influenced by the Greek city-state model during the first two centuries AD. The city became a Roman colonia during the third century, leading to the incorporation of Roman governing institutions, before becoming a monarchy in 260. Following its destruction in 273, Palmyra became a minor center under the Byzantines and later empires. Its destruction by the Timurids in 1400 reduced it to a small village. Under French Mandatory rule in 1932, the inhabitants were moved into the new village of Tadmur, and the ancient site became available for excavations. During the Syrian civil war in 2015, the Islamic State captured Palmyra and destroyed large parts of the ancient city, which was recaptured by the Syrian Army on 2 March 2017.

While reading the inscriptions in Palmyra, one has the impression that in time the city became increasingly familiar with Rome and its institutions, with the complicated hierarchy of its power, and that it became a city like others, a true city of the empire.[1]

- ^ Veyne, Paul; Fagan, Teresa Lavender (2017). Palmyra. University of Chicago Press. p. 39. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226452937.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-60005-5.